Prologue

On Saturday, September 27, 1856, Colonel Roswell B. Mason, engineer-in-chief for the Illinois Central Railroad Company, notified the railroad’s board of directors in New York City that the final spike was driven in, securing the last rail to complete the 705 miles of the longest built railroad in the world up to that time. The Illinois Central Railroad Company, or Illinois Central, was chartered by the Illinois General Assembly on February 10, 1851, making it the first of the federal land-grant railroads in the United States. On March 22, 1851, the Illinois Central’s board of directors chose Col. R. B. Mason of Bridgeport, Connecticut as its chief engineer. Construction on the railroad began on Christmas day, December 25, 1851.

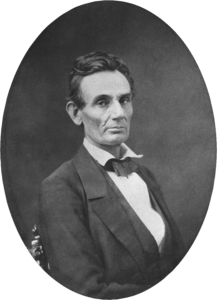

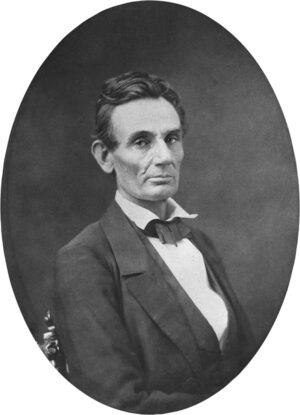

In February of 1856, the Honorable Abraham Lincoln, an able circuit court and railroad lawyer from Springfield, Illinois with political aspirations for himself and his political party, won a crucial victory for the Illinois Central in the state Supreme Court case, Illinois Central RR v. McLean County, Illinois. The railroad was suing the county, claiming their railroad charter exempted them from county property taxation because the railroad was already paying a percentage of their revenue to the state. Lincoln would spend the rest of 1856 trying to get paid by the Illinois Central for his successful defense of Illinois Central RR v. McLean County. That year, he would also convince one of his oldest friends, Jesse Dubois, to join the Republican Party and run for State Auditor, while Lincoln set his sights on 1858 and the U.S. Senate seat held by the “Little Giant,” Stephen A. Douglas.

Lincoln was a long-time supporter of the Illinois Central and its predecessor, the Cairo City & Canal Company, going back to his early days in the Illinois Legislature. He was hired by the organizing company to help lobby for the passage of the state charter in 1851 and worked for the company in one capacity or another until his Presidency. Lincoln first represented the railroad as an attorney under legal retainer on April 16, 1853 in the case of Howser v. Illinois Central Railroad, tried in Bloomington, McLean County, Illinois. Lincoln was hired to defend the railroad when Jonathan Howser appealed an award for property damage caused by the Illinois Central. Lincoln and the railroad lost the appeal. Mr. Lincoln’s biggest court case for the railroad, although not that well known, occurred in Illinois Supreme Court on November 18 and 19, 1859, in the People v. Illinois Central Railroad.

The People v. Illinois Central Railroad

The People v. Illinois Central Railroad was a case that was three years in the making in which Abraham Lincoln was caught between his primary source of income in the 1850’s, the Illinois Central Railroad, and a close political ally and warm personal friend, Illinois State Auditor Jesse K. Dubois.

Freshman State Auditor Dubois had been threatening to file a lawsuit against the Illinois Central for back taxes due even before the Illinois Central paid the first installment on their semi-annual tax bill as defined by the state charter, with payments to start in October of 1857. The state charter under which the Illinois Central operated and was to be taxed was open to interpretation. The State Auditor had made it known early on that he interpreted it one way, and the railroad made it known they interpreted it another. The State Auditor assessed the value of the Illinois Central Railroad using a different assessment method than the one used to value all other railroads operating in the state. Dubois placed the assessed taxable value of the Illinois Central at $19,711,559.59. The Illinois Central’s 1857 replacement for Roswell B. Mason, engineer-in-chief and company vice president, Captain George B. McClellan, believed the railroad was being assessed four times the rate of any other railroad operating in the state, and believed the valuation to be more accurately reflected at $4,942,000.00. McClellan and the railroad board of directors also knew that the Illinois Central was financially in trouble, and with a looming depression and the Panic of 1857 on the horizon, could not afford to pay the state taxes on a property assessment they believed to be inflated and unfair.

In May of 1857, Illinois Central president William H. Osborn, in counsel with Illinois Central resident director of the Law Department, Ebenezer Lane, a former justice of the Supreme Court of Ohio, decided to induce Lincoln to use his personal friendship with State Auditor Dubois to help buy the railroad some time with its tax troubles. The Illinois Central had a problem, however. The railroad still had not paid Lincoln for his work from 1853 to 1856 on the case, Illinois Central RR v. McLean County, Illinois. After nearly a year of trying to collect the fees Lincoln felt were owed to him by the railroad, he filed suit in Abraham Lincoln v. Illinois Central Railroad in January 1857.

Mr. Lane had also informed Mr. Osborn that State Auditor Dubois had offered to put Lincoln on the payroll as lead counsel for the state in the impending court battle that would lead to People v. Illinois Central Railroad. This was an attractive proposition to Lincoln as he was in need of revenue as he fought his own battle with the railroad for past-due fees. Osborn knew the railroad needed to act quickly to win over the most able lawyer and politician in all of Illinois. Osborn and the railroad worked out a compromise with Lincoln. If Lincoln would reject Dubois’ offer and defend the railroad, the railroad would not contest or defend Abraham Lincoln v. Illinois Central Railroad and would pay Lincoln his full asking price at the end of the case in a couple of months. Lincoln found the appeal of receiving a much needed $4,800 dollars desirable and agreed to the Illinois Central’s offer.

Lincoln & Dubois

Jesse K. Dubois and Abraham Lincoln’s friendship began in the early days of their political careers in the Illinois House of Representatives, from 1834 to 1842. Both men were active power brokers in the emerging state Republican Party Central Committee in the 1850’s. Lincoln first befriended Dubois when they served their freshmen year together in the Illinois State Legislature in 1834. Lincoln convinced his old Whig friend to join the Illinois state Republican Party in 1856 and helped get him elected State Auditor in that year. Dubois and his family moved to Springfield in 1856, just a few doors down from the Lincolns on Eighth Street. The Lincolns and the Dubois’ would spend countless hours at each others’ homes and would vacation together.

From the moment Dubois took over as State Auditor of Public Accounts on January 12, 1857, he had been publically scrutinizing the taxable assessment value of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, Illinois’ largest corporation, under the provisions of their state charter. On October 9, 1857, in anticipation of their first semi-annual tax payment coming due on October 30th, the Illinois Central suspended all payments of debt and was assigned to a three-member trusteeship for financial restructuring. On October 22nd, Auditor Dubois levied his tax assessment for 1857 against the railroad with a payment of $86,449.02 due in eight days. October 30th came and passed without a tax payment to the state by the railroad.

On December 21, 1857 Lincoln found himself writing his old friend Dubois on behalf of the Illinois Central Railroad, not as a railroad lawyer to the State Auditor, but rather as a lawyer providing his personal opinion to “a friend.” Lincoln wrote to Dubois, “J.M. Douglas of the I.C.R.R. Co. is here and will carry this letter. He says they have a large sum (near $90,000) which they will pay into the treasury now if they have an assurance that they shall not be sued before January, 1859 – otherwise not. I really wish you would consent to this. Douglas says they cannot pay more and I believe him. I do not write this as a lawyer seeking an advantage for a client, but only as a friend, urging you to do what I think I would do if I were in your situation…” John M. Douglas was an old Galena, Illinois mining lawyer who was now the Solicitor for the Illinois Central, and one of Lincoln’s closest allies and political supporters within the Illinois Central Railroad corporate structure.

Dubois opted to go with the advice of his friend Lincoln and agree to the proposed terms and receive the $86,000 from the Illinois Central into the state treasury. This was a wise move given the stock market had crashed three months earlier and the Panic of 1857 had begun. The railroad industry and railroad stocks were one of the hardest hit industries during and after the Panic started in September of 1857, as passenger and freight travel, along with revenues, started to rapidly drop across the country.

1858

Jesse K. Dubois remained relatively quiet about the Illinois Central throughout the majority of 1858. Dubois did this due in large part to the December 1857 agreement he made with John M. Douglas and the railroad through Lincoln. Dubois also did it in large part to help Abraham Lincoln in his efforts to become the first Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Illinois. Lincoln faced off against incumbent U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas (D-IL) in a series of debates throughout Illinois in 1858 known as the Lincoln-Douglas Debates.

The debates were held in Ottawa, Illinois on August 21, 1858, Freeport on August 27th, Jonesboro on September 15th and then in Charleston on September 18th. The debates picked back up in Galesburg, Illinois on October 7th, Quincy on October 13th and the last of the great debates in Alton, Illinois on October 15th. The Illinois Central ran special trains from Chicago, Galena, Springfield and other locations to and from the debate sites. As the debates raged on in Illinois, the nation started to take notice of the Illinois “prairie” lawyer. But not everyone was a fan of Mr. Lincoln.

Illinois Central vice president George B. McClellan, for one, was a supporter of his fellow Democrat Stephen A. Douglas. Like all the other Illinoisians, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas traveled to and from the debate sites predominately by the Illinois Central Railroad. McClellan offered Senator Douglas the use of his Illinois Central corporate executive car, equipped with a sleeping berth, a dining room and other luxuries not found in common coach. No such offer was made to Mr. Lincoln. Lincoln did have a free pass on the Illinois Central as part of the benefit of being a corporate lawyer on retainer for the company. He did not, however, have access to a private car, for debates or otherwise, as a corporate lawyer for the railroad.

Although Lincoln performed well in his debates against the “Little Giant” and gained favor within the national Republican Party, and among voters around the nation, he did not come out victorious in the November 1858 election to unseat U.S. Senator Stephan A. Douglas. Jesse Dubois had taken notice of the preferential treatment given to Douglas by McClellan, and he believed by the Illinois Central Railroad, during the debates. Dubois also noticed the treatment was not offered in-kind to his friend, Abraham Lincoln, so much so that the day after Stephen A. Douglas was re-elected U.S. Senator, Illinois State Auditor Jesse K. Dubois filed a legal brief against the Illinois Central Railroad Company in the state Supreme Court for back-taxes owed for 1857.

On February 1, 1859, the state Supreme Court case People v. Illinois Central Railroad was officially set to be heard on November 18th of that year in Mount Vernon, Illinois, where the Illinois Supreme Court would be holding session.

Planning the Defense

The railroad turned to Lincoln to lead their defense in People v. Illinois Central Railroad. Lincoln and his law partner William Herndon successfully defended the Illinois Central Railroad in a tax case brought by the railroad against McLean County, Illinois in August of 1853. The railroad hoped this time would be no different.

On Tuesday, April 26, 1859 George B. McClellan was in Dubuque, Iowa on railroad business, staying at the Julien House. He departed Dubuque on April 27th. McClellan, vice president and chief engineer of the Illinois Central, was most-likely in Dubuque meeting with his predecessor at the Illinois Central and setting the stage for a future visit by railroad officials, including Lincoln.

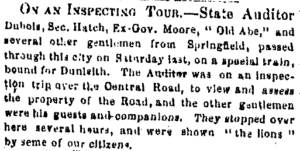

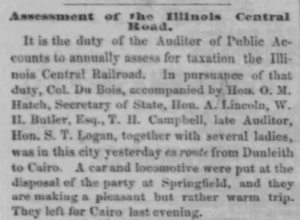

McClellan, Lincoln and the railroad executives organized a nine day tour set for July so state officials could inspect every mile of railroad track, and all the properties owned by the Illinois Central Railroad, in a process of discovery in the case People v. Illinois Central Railroad. The railroad hoped the state and the railroad would come to a mutually agreeable valuation more in line with the railroad’s estimates for the 1859 tax year. It was decided that Lincoln, as corporate lawyer and lead counsel for the case, would lead the tour. Lincoln would bring along Illinois Central board of director member and company trustee John Moore. The trip was promoted as the State Auditor assessment tour of the Illinois Central, which was his legal duty under the state charter. The Freeport Weekly Journal headline declared, “On an Inspecting Tour – State Auditor”. The Chicago Tribune headline read, “Assessment of the Illinois Central Road” and pointed out the “duty of the Auditor of Public accounts to annually assess for taxation the Illinois Central Railroad.”

The railroad decided to make the trip a bit more enjoyable for the travel party by allowing everyone to bring their families. To ensure the party was able to effectively conduct railroad business, the board of directors provided a private locomotive with a private car; presumably the executive car McClellan had allowed Senator Douglas to use during the Lincoln-Douglas debates just ten months prior.

The assembled travel party consisted of railroad executives, state officials and appraisal experts, with most everyone having a close connection to Lincoln. On the trip were Jesse K. Dubois, State Auditor; Ozias M. Hatch, Secretary of State; William H. Butler, State Treasurer; former state Lt.-Governor John Moore, an Illinois Central board member; Thomas H. Campbell, former State Auditor; and in a role originally offered to Lincoln was Judge Stephen T. Logan, special counsel for the state. Jesse Dubois, Stephen Logan, and Thomas Campbell brought their wives with them on the trip. Mary Todd Lincoln joined her husband on the trip along with the Lincoln’s two youngest sons William, or Willie, and Thomas, or Tad Lincoln.

From the outside, the trip appeared more a vacation among old friends than state railroad business, and Abraham Lincoln was the common denominator. Lincoln had known William Butler since his early days in New Salem, and lived with Butler and his family for over five years. He first met Dubois in the state legislature in 1834. Ozias Hatch and Lincoln worked closely as political comrades in Illinois state politics. Lincoln was a frequent visitor to Hatch’s office in Springfield when he was Secretary of State and would take Hatch’s personal clerk, John G. Nicolay, to Washington, D.C. to be his personal secretary in the White House. Butler, Dubois, Hatch and Lincoln, along with Illinois Civil War governor Richard Yates, were the real power-brokers of Illinois Republican politics during its infancy. Judge Stephen T. Logan, who was on the trip as special counsel to the State Auditor, was once Lincoln’s law partner in Springfield, from 1842 to 1844, and had known and worked with Lincoln before and after their partnership. Mary Todd Lincoln was especially fond of Mr. Hatch and of Mrs. Dubois.

Traveling the Illinois Central

On Thursday, July 14, 1859, the travel party, including the future President and his family, boarded the private train provided for the trip and departed Springfield, Illinois to assess the lines and property of the Illinois Central Railroad. In 1859, the Illinois Central Railroad started at the southern tip of Illinois in Cairo and ran north through Jonesboro, Carbondale and into Centralia, Illinois, east of St. Louis. In Centralia, the Illinois Central split into two lines, with the Chicago Line running to the northeast and into Chicago. The Galena, or Main Line ran north through the prairies of Decatur, Bloomington, La Salle, and into Dixon. From Dixon, the line contoured the rolling hills all the way to Freeport. From Freeport, the line cuts through the deep valleys and the high bluffs around Galena, and on into the northern terminus of the Illinois Central Railroad in the river town of Dunleith, Illinois, across the Mississippi River from Dubuque, Iowa. (Dunleith is the present day city of East Dubuque, Illinois.)

The party set out from Springfield to Decatur along the Western Railroad. In Decatur they merged onto the Illinois Central Railroad lines and headed north for Dunleith in the northwestern part of the state. The party could only travel 13 hours a day, all during daylight hours, so the lines and railroad property could be observed and assessed. This trip would be especially brutal as daytime temperatures ranged from 98 to 108 degrees around Illinois and Iowa that week. Based on Illinois Central Railroad timetables, the party would require approximately 16 hours of travel time from Springfield to Dunleith, broken up over two days to accommodate for daylight travel, with frequent stops to assess properties and load up on fuel and water for the locomotive.

On Saturday, July 16th, the Lincoln private train rolled into Freeport, Illinois for a stop. The Freeport Weekly Journal stated on July 21st, “Dubois, Sec. Hatch, Ex-Gov. Moore, “Old Abe,” and several other gentlemen from Springfield, passed through this city on Saturday last, on a special train, bound for Dunleith.” “They stopped over here for several hours, and were shown ‘the lions’ by some of our citizens.” After departing Freeport, the party would have stopped in Galena to assess the Illinois Central station and properties there. From Galena it was on to the northern most terminus of the Illinois Central in Dunleith. It is not hard to imagine Lincoln telling Willy and Tad stories of his days as a captain in the Black Hawk War as the locomotive rolled through the rock cuts and high bluffs of northwestern Illinois, between Freeport and Galena. Or about the day in 1856 he gave a speech to a large crowd in the streets from the second floor balcony of Galena’s DeSoto House. Or even stories of the Meskwaki Indian village at Dubuque’s lead mines, when wild natives and beasts still roamed the prairies of Illinois and Iowa, once upon a time.

Upon reaching the railroad station in Dunleith on Saturday, July 16th, the travel party prepared for a stopover in nearby Dubuque, Iowa for Sunday observance. Lincoln, along with Mary and the children, and the rest of the travel party, disembarked from the train at the station at the end of Sinsinawa Avenue in Dunleith. Grabbing some of their personal belongings for their stay in Dubuque, the party started to make their way towards the Mississippi River to cross over into Dubuque. In 1859, the closest railroad bridge crossing the Mississippi River from Illinois into Iowa was between Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa. Travelers and cargo transported on the Illinois Central Railroad to and from Dubuque through the Dunleith terminal had to cross the Mississippi River at Dubuque by river ferry until January of 1869, when the Dunleith & Dubuque Railroad Bridge opened. The Lincoln party was no exception. Like all other travelers and cargo, the thirteen member Lincoln party traveled the 1,000 feet from the Illinois Central station to the Dubuque & Dunleith Ferry landing on the eastern banks of the Mississippi River, directly across from the Dubuque Harbor and Jones Street, on the western banks of the Mississippi River.

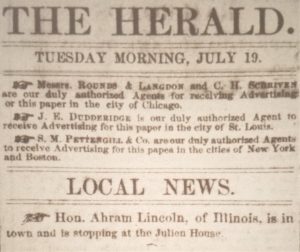

After crossing the river on the Dubuque & Dunleith Ferry, the party, having secured a ride on the Iowa side, would head west on Jones Street, turning north onto Main Street and heading three blocks to the Julien House, Dubuque’s premier hotel. Unlike many of the trips he was making between 1856 and 1860, Lincoln did not make a public or political appearance while in Dubuque. It is unknown what the party did while in Dubuque. Whether Mary Todd Lincoln and her two boys were out and about in Dubuque to explore the rapidly growing Key City to the Northwest, or took in a show at one of Dubuque’s theaters, we do not know.

A young Dubuque railroad lawyer and Iowa Republican by the name of William Boyd Allison heard that the great Illinois Republican from the Lincoln-Douglas debates was in town. Most likely Allison and others had learned of Mr. Lincoln’s arrival by the conspicuous presence of a private locomotive and coach parked in Dunleith, and the news – and rumors – that spread with its arrival. Allison wished to see Lincoln in the flesh. So Allison, along with some other enthusiastic young Republicans, including his law partner George Crane, went to the Julien House to see if they could catch a glimpse of the great debater, who was only seven months away from giving his lynch-pin speech at Cooper Union in New York City that would launch him directly into the White House. Allison would later say, “When I heard he was in town, I went to the hotel to see him. However, I didn’t feel important enough to make his acquaintance.”

The Dubuque & Pacific Railroad

Living in Dubuque at the time of Abraham Lincoln’s visit in July of 1859 was none other than Colonel Roswell B. Mason, George B. McClellan’s predecessor as engineer-in-chief of the Illinois Central Railroad. Mason had moved to Dubuque in 1856, after completing the Illinois Central, in order to start construction on the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad, from Dubuque to Dyersville, Iowa. Mason had signed on as the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad’s chief engineer from the railroad’s beginning on April 28, 1853, while he was still engineer-in-chief and superintendent of the Illinois Central Railroad. Mason, along with Illinois Central president Robert L. Schuyler, were original members of the group of individuals who first organized and incorporated the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad.

Lead by Lucius H. Langworthy, an original founder of the city of Dubuque in 1833, the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad was formally incorporated on May 19, 1853. Langworthy was joined by Mason and Schuyler along with Jesse P. Farley, the railroad’s first president; Platt Smith, the railroad’s attorney; Frederick S. Jesup, the railroad’s treasurer and brother of Morris Ketchum Jesup, a prominent New York banker and railroad investor; Judge John J. Dyer, F.V. Goodrich, Robert Walker, Robert C. Waples, Edward Stimson, Capt. G.R. West, Dr. Asa Horr and Mordecai Mobley, a Dubuque banker, early settler of Sangamon County, Illinois, and friend of Abraham Lincoln; and United States Senator George Wallace Jones (D-IA), the railroad’s first Chairman of the Board.

George Wallace Jones, while serving a term as U.S. Representative for the Wisconsin Territory in 1838, was the first Congressman to propose appropriating federal funding to build a transcontinental railroad, connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. The idea was based on the request, research and planning done by Jones’ Dubuque constituent, John Plumbe Jr. Plumbe, a civil engineer, is believed to be the first person to propose and actively work for a transcontinental railroad in America.

Jones next played a critical part in U.S. railroad history when, as a U.S. Senator, he was successful in amending Sen. Stephan A. Douglas’ Federal Land Grant Act of 1850, which provided federal land to the state of Illinois for the creation of the Illinois Central Railroad. Jones’ amendment extended the proposed terminus of the Illinois Central from Galena, Illinois to Dubuque, Iowa by way of Dunleith, Illinois. The successful passage of Jones’ amendment upset the citizens of Galena and created friction between Sen. Douglas and the people of Galena in the 1858 U.S. Senate race. During the Senate race between Lincoln and Douglas, Douglas accused his fellow Democrat, Sen. Jones, of underhanded politics in getting the terminus of the Illinois Central extended from Galena to Dubuque back in 1850. Jones took offense to the accusations and came out in support of Douglas’ opponent, Abraham Lincoln, for Senate in 1858.

Roswell B. Mason

The Dubuque & Pacific Railroad was conceived as a natural extension of the Illinois Central Railroad, connecting the eastern and western sides of the Mississippi River, allowing the Illinois Central to extend its presence into Iowa and on to the Pacific Ocean and allowing the Dubuque & Pacific to connect with the markets of the east coast. The plans also called for a railroad bridge to be built across the Mississippi River at Dubuque, connecting the Dubuque & Pacific directly to the Illinois Central. The bridge came close to becoming a reality on February 14, 1857 when the Illinois State Legislature approved a charter for the Dunleith & Dubuque Bridge Company. And engineer Roswell B. Mason was to be the architect of it all. The construction of a railroad bridge was delayed by more than a decade due to the Panic of 1857, the depression that followed, and the events of the American Civil War.

Mason moved to Dubuque after resigning as chief engineer from the Illinois Central and the Dubuque & Pacific Railroads in 1856. Mason, along with his partner Ferris Bishop, started Mason, Bishop and Company, a railroad construction company, which in turn was hired by the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad to prepare the route, build the bridges and lay the tracks for the railroad from Dubuque to Dyersville, Iowa. Mason, Bishop and Company was located in the same building as the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad in the Julien Theater building at the northwest corner of 5th & Locust Streets. Replacing Mason as chief engineer of the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad in 1856 was one of his associate engineers responsible for building the Illinois Central from Eldina, Illinois, near La Salle, to Dubuque – Benjamin B. Provoost.

It is likely Lincoln and John Moore, along with the state officials, met with Col. Mason and Benjamin Provoost during their visit to Dubuque. There is a strong possibility the meeting was preplanned during George B. McClellan’s visit to Dubuque less than three months prior. Mason’s office was only four blocks from where the Lincoln party was staying in Dubuque and it would not have been the first time Lincoln and Mason had met. Nor would it be the last. Both men had worked at the pleasure of the board of directors of the Illinois Central Railroad since the early 1850s.

Col. Mason was a key witness called by Lincoln in his landmark case Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company in 1857. The case revolved around Jacob S. Hurd and his steamboat the “Effie Afton.” Hurd had struck two bridge piers as he tried to navigate the Effie Afton past the first ever railroad bridge across the Mississippi River, between Rock Island, Illinois and Davenport, Iowa. The boat was destroyed and the bridge was damaged by the incident. Hurd claimed in his lawsuit that the bridge presented an obstruction to the free navigation of the Mississippi River, and therefore the bridge company was responsible for the damages to his steamboat. The Rock Island Bridge Company hired Lincoln to defend them. Lincoln enlisted the aid of an eminent civil engineer living in Dubuque – Roswell B. Mason – to help build the defense. Mason testified over the course of two days in the case and described his experience building railroad bridges in the East and throughout Illinois. Mason described a series of tests and experiments he conducted with floats to evaluate the flow and current of the river in regard to the placement of the bridge piers at Rock Island. He related these experiments to piloting a steamboat, navigating the river currents and the ability for railroad bridges and steamboats to successfully coexist in the Mississippi River through intelligent engineering design. It was this testimony that helped Lincoln win this case critical to railroads across the nation.

Roswell B. Mason would also go on to be one of three key witnesses Lincoln would call to testify in the Illinois Supreme Court case People v. Illinois Central Railroad in November of 1859. This is the case that led the Lincoln travel party to assess all the lines and properties of the railroad, and the case that lead Lincoln to Dunleith, and to Dubuque.

Lincoln Departs

Lincoln and his travel party left Dubuque and Dunleith on Monday morning, July 18th. Just four short years prior, on July 18, 1855, U.S. Senators George Wallace Jones (D-IA) and Stephan A. Douglas (D-IL) were in Dunleith to dedicate the grand opening of the Illinois Central line from Eldena to Dunleith and the arrival of the first train a few weeks earlier.

The travel party arrived in Chicago later that Monday evening. The Chicago Tribune noted in its “Personal” section that the party checked into the Tremont House, located at the southeast corner of Lake Street and Dearborn in downtown Chicago. After spending Tuesday, July 19th in Chicago, the party left for Cairo, Illinois, at the southern tip of the state. The Lincoln travel party finally arrived back in Springfield late on Friday, July 22nd, successfully wrapping up a nine day, 705 mile tour of the properties of the Illinois Central Railroad.

Epilogue

Abraham Lincoln would go on to successfully defend the Illinois Central Railroad Company in the case People v. Illinois Central Railroad, appearing before the court in Mount Vernon, Illinois on November 18th and 19th, 1859 to address the railroads assessment value for the 1859 tax year. Lincoln appeared before the court again on January 12, 1860 to address the outstanding issue of back taxes due for 1857 and 1858. Lincoln’s three key witnesses in the case were Illinois Central vice president George B. McClellan, former Illinois Central chief engineer Roswell B. Mason, and the then current railroad chief engineer of the Illinois Central, Leverett H. Clarke. The High Court handed down its decision on the company assessment valuation on November 21, 1859, finding in favor of Mr. Lincoln and the Illinois Central Railroad. The Court handed down its decision on the company’s back taxes for 1857 and 1858 in February of 1860, again finding in favor of Lincoln and the railroad.

Abraham Lincoln would give his Cooper Union speech in New York City seven months after visiting Dunleith and Dubuque. From there he would go on to beat Stephan A. Douglas in the 1860 presidential election, becoming the 16th President of the United States on March 4, 1861.

George B. McClellan would go on to become President Lincoln’s Commanding General of the U.S. Army on November 1, 1861, at the beginning of the American Civil War. President Lincoln relieved General McClellan of his command on November 5, 1862 for not pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam. McClellan would go on to lose to President Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election as his Democratic challenger.

Jesse K. Dubois, Ozias M. Hatch, and William H. Butler worked selflessly to get their friend Lincoln elected President in 1860. They each remained active in Illinois Republican politics and continued to communicate with their long-time friend and comrade, President Lincoln, on state and national political matters. Jesse Dubois would eventually become cynical about a lack of personal political favors from President Lincoln, but would always remain loyal to Lincoln the man, and his memory. Dubois would play a key role in bringing the martyred President back to Springfield, Illinois in 1865 and seeing him buried on behalf of his grieving friend, Mary Todd Lincoln, who was too crippled by grief to participate. Ozias Hatch was with President Lincoln in October of 1862 and accompanied him on a visit to the Antietam battlefield to see General McClellan. It was to Hatch during this visit that Lincoln referred to the Army of the Potomac as “General McClellan’s bodyguard”. Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Dubois and Ozias Hatch joined Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln when they visited Council Bluffs, Iowa in August of 1859, one month after their visit to Dubuque.

U.S. Senator George Wallace Jones would unburden himself of his interests in the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad under the restructure that resulted after the Panic of 1857. The Dubuque & Pacific would reorganize as the Dubuque & Sioux City Railroad in 1860, which ultimately became the property and primary line through Iowa for the Illinois Central Railroad. Jones would also sell some of his riverfront property in Dunleith to the Illinois Central Railroad for the construction of a railroad bridge between Dunleith and Dubuque. Jones received a lifetime pass on the Illinois Central Railroad for himself and his family as part of his compensation for the land. The Dubuque lawyers representing the Illinois Central in the land sale were none other than George Crane and U.S. Rep. William Boyd Allison (R-IA). Rep. Allison was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1862 and developed a working relationship with President Lincoln during his administration. Allison was also the president of the Dunleith & Dubuque Bridge Company. Both Jones and Allison met with President Lincoln in the White House during the Lincoln Administration.

The chief engineer Allison selected to oversee the construction of the Dunleith & Dubuque Railroad Bridge in 1867 was none other than Roswell B. Mason, the builder of the Illinois Central and Dubuque & Pacific Railroads and Lincoln’s star witness in two of his most important railroad cases as a corporate lawyer. Mason served as the original chief engineer for the Illinois Central Railroad Company, the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad Company and the Dunleith & Dubuque Bridge Company. He also served as Superintendent of the Illinois Central and President of the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad at one time or another. With the completion and opening of the Dunleith & Dubuque Railroad Bridge in 1869, Mason resigned from the company and moved back to Chicago.

Roswell B. Mason was elected mayor of Chicago in November of 1869. Mayor Mason was at the end of his term when the tale tells of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicking over a lantern and starting the Great Chicago Fire on October 8, 1871. Mayor Mason sent telegraphs to his friends in nearby cities, including the city of Dubuque, requesting immediate assistance of any kind. The call went out to Dubuque, Milwaukee, Detroit and other Midwest communities. City of Dubuque officials immediately provided Mason with $2,500 in cash from the city treasury and the citizens of Dubuque sent food, clothing and other necessities over the next couple of months.

All of the Dubuque donations for the Great Chicago Fire were delivered over the railroad bridge and tracks Roswell B. Mason personally built over the prior two decades of his life, the same railroad tracks that brought an influential railroad lawyer named Abraham Lincoln to Dunleith and Dubuque in July of 1859!

Copyright – 2018 – The Lens of History – John T. Pregler. This story cannot be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without prior authorization from the author or The Lens of History.

Fantastic research and an excellent reporting of it. Congratulations, John.

Excellent writing and research. Enjoyed it greatly. Thanks for the many hours involved!