The following article first appeared in the Fall 2022 edition of the Society of American Baseball Research’s (SABR) Baseball Research Journal. The original article can be accessed at sabr.org by CLICKING HERE.

AN AMERICAN LEAGUE BIRTHDAY

On January 10, 1918, The Sporting News published an article tucked away on page five celebrating the American League’s birthday. “If you are a believer in the Darwinian theory of evolution, then January 2 should be a day of interest to you for it marks the ‘birth of the American League,’ which according to the Darwinian baseball historians is now 39 years of age. It is this way: On January 2, 1879, the old Northwestern League was formed. Out of it grew the old Western League, which in time became the American League of today,” explained the paper. “But it is a far cry. The connection may be there, but it is as close as saying that a she-ape in the African jungle was the grandmother of the Queen of Sheba.” Outlining the following “evolution” of the American League in a few sparse paragraphs, The Sporting News suggested the AL descended from the Northwestern League of 1879:

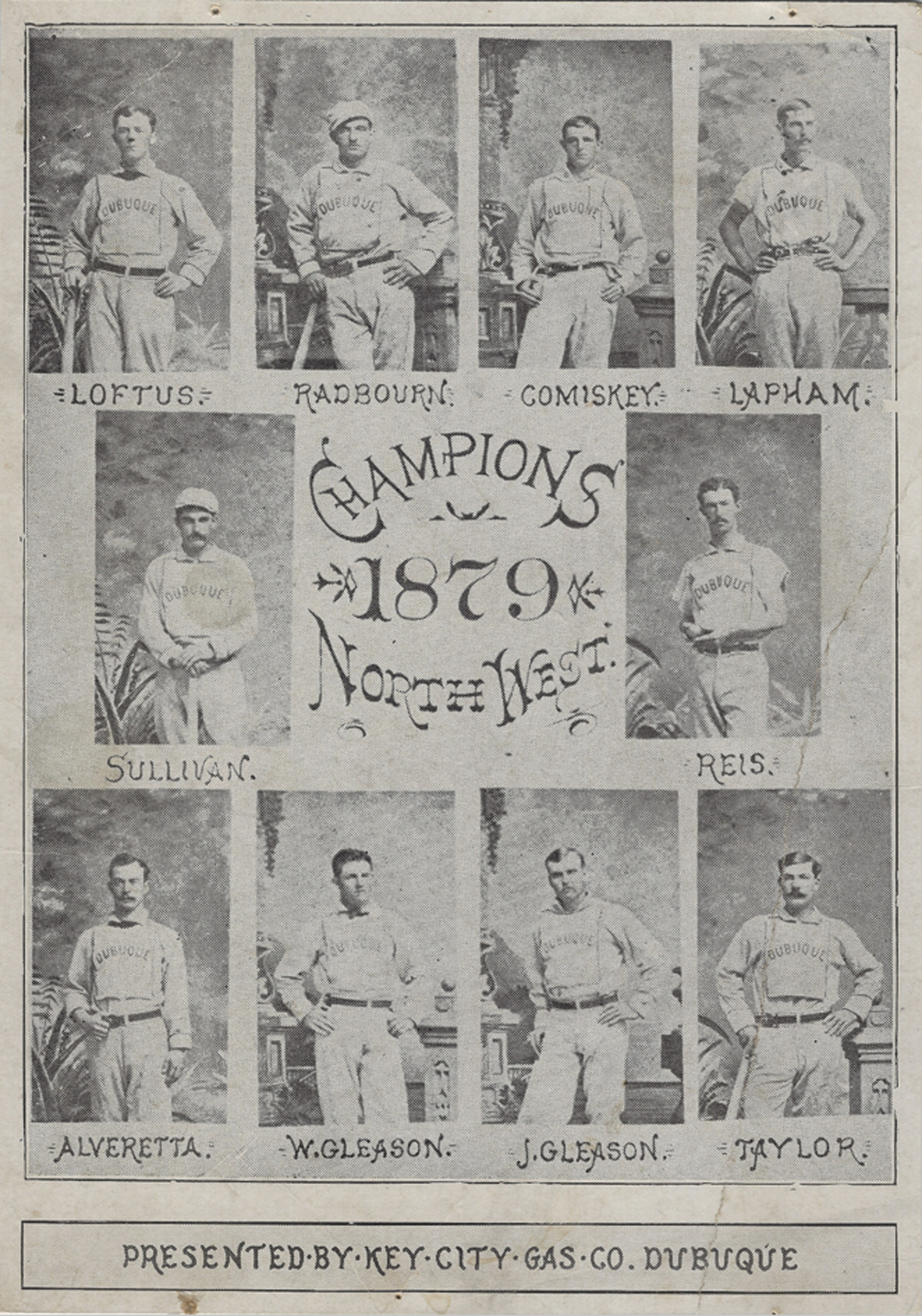

Dubuque won the first pennant, the Iowa city’s players including Charley [sic] Comiskey, then a pitcher; Charley Radbourne [sic], Ted Sullivan and Tom Loftus. The original Northwestern lasted only one season, but it was revived in 1883 with a bunch of cities… In 1888 the name was changed to the Western Association, and in 1892 the circuit became the Western League and remained such until 1899. Toward this period Ban Johnson enlarged the circuit and in 1900 the name was changed to the American League.

The lines between the Northwestern League, Western Association, Western League, and American League are not made any clearer in the four-paragraph piece. Although not an “evolution” of direct descendants as The Sporting News suggests, the relationship between the Northwestern League and the American League is closer than the she-ape is to the Queen of Sheba. In fact, it is as close as three intimate friends with a lifelong love affair with building up the early game of professional baseball.

Sullivan, Loftus, and Comiskey made up the heart of the original Northwestern League’s Dubuque Red Stockings (aka Rabbits). Their association with each other is the common thread that runs between the professional leagues that ultimately evolved into the Western League of 1894–99, and then into the American League, for which Comiskey is enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, along with Ban Johnson. In a previous paper I have written about Loftus and discuss his and Comiskey’s roles in establishing the American League. The lead-up to the establishment of the American League as a major league between 1899 and 1903 was not by a planned or continuous progression of a singular entity or vision, but rather was preceded by a process of “natural selection,” in which different leagues attempted to adapt successfully to their changing baseball environment.

Distorted history by early biographers would place all the credit for the formation of the American League on Ban Johnson with a strong nod to fellow Hall of Famer Comiskey. At the time of the Sporting News article in 1918, Comiskey was in the middle of his now-notorious feud with AL president Ban Johnson as each man tried to fashion public opinion regarding their respective role in the rise and success of the American League prior to 1920. Comiskey’s official biographer, G.W. Axelson, disputed the Sporting News article’s loose assertion on the evolution of the American League when he published “Commy: The Life Story of Charles A. Comiskey” in 1919. In the biography, Axelson goes so far as to suggest the founding of the AL was solely Comiskey’s plan, stating, “The move had been conceived by Comiskey nine years before its actual consummation” in 1899. Axelson went on to state, “The fact remains that it was the Western League, founded in 1894 which was expanded into the American League in 1900. The original Northwestern League, organized in 1879, and the Western Association, founded in 1888, cannot claim relationship.” There is no denying the newly minted American League of 1900 was the result of a name change of the existing Western League of 1899, which had been reorganized under a newly elected president, Ban Johnson, in 1893 for its 1894 season; it is also recognized that the American League of 1901—the AL’s first season as a major league—evolved from the 1900 minor league AL. At best it could perhaps be said that the AL is a relative of the old leagues without being direct progeny. Only two teams from the 1899 Western League—Milwaukee and Detroit—remained to see the 1901 American League season. Six of the eight teams in Johnson’s 1894 Western League season had played in the Western Association (aka Western League) between 1888 and 1893.

Axelson’s argument seems to assume there was no Western League prior to 1894 and that Ban Johnson helped create a new league out of thin air, when in reality he was brought in after the reorganizing work was complete, and then elected president at the urging of Comiskey and John T. Brush. The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette reported on the October 25, 1893, meeting at the Grand Pacific Hotel in Chicago. In an article entitled, “Reviving the Western League,” the Gazette opens the article: “The Western Base Ball Association is being revived today at a conference at the Grand Pacific Hotel. Organized in 1884, the Association was continued until last year…” The Gazette article interchangeably referred to the Western League and the Western Association, adding to the confusion of the evolutionary story. Axelson may have also denied any potential relationship because Comiskey did not have claim to direct involvement in the founding of the Northwestern League or the Western Association, although we will later see that he did have an interest in the Western Association.

NORTHWESTERN LEAGUE

The American League’s genesis, as suggested by the Sporting News article, begins with the organization of the first Northwestern League for their 1879 championship season—and Timothy Paul “Ted” Sullivan. Sullivan, a Dubuque businessman and the league’s treasurer, along with James McKee of Rockford, Illinois, the league’s president, co-founded the league in late 1878. Organizing a professional baseball league includes countless tasks, including organizing the league office, recruiting cities and ball clubs with the financial support to sustain their team and the league, ensuring interested clubs have adequate playing grounds, finding quality players to fill the teams and providing new players as needed, developing agreeable travel schedules, etc. Sullivan organized his first league which included Omaha, Rockford, Davenport, and Dubuque. The Northwestern League of Base Ball Clubs was the first league to use the name Northwestern League in baseball. It was the first professional league west of the Mississippi River and the second professional league in baseball history after the National League (1876–present). Milwaukee, member of the 1878 National League, entertained joining the 1879 Northwestern League. Milwaukee had struggled to meet all its debt obligations from the 1878 NL season, was forced to liquidate, and were therefore unable to re-sign their top players for 1879. Rockford signed four players from the 1878 Milwaukee team, creating the nucleus of their team for the new league. Sullivan signed most of the Peoria Reds team for Dubuque, adding captain Loftus, Charley Radbourn, and brothers Jack and Bill Gleason to the nucleus of his Red Stockings team, which already included pitcher Comiskey.

The first Northwestern League pennant was taken by Sullivan, Loftus, Comiskey, and the Dubuque Red Stockings. The National League took notice of Sullivan, his league, and his team when his Dubuque Red Stockings beat Adrian “Cap” Anson and his powerhouse NL Chicago White Stockings in Dubuque by a score of 1–0. Sullivan and the other team owners in the league quickly learned how cash intensive running a professional baseball club and league was: The league was unable to return in 1880 for financial reasons. Upheaval was not uncommon at the dawn of early professional baseball. Early teams often changed leagues from one season to the next, or even within the same season. Sometimes teams dropped out of a league mid-season, and new teams or cities took their place. Loftus managed Milwaukee in the 1884 Northwestern League. When the league’s season ended, Loftus then took Milwaukee into the major-league Union Association to replace Wilmington, who could not finish their season. The next year, 1885, Loftus and Milwaukee would join the inaugural class of the Western League. This kind of movement was commonplace among leagues, cities, and teams throughout the nineteenth century.

When a team or league would fail—whether due to poor financial performance or poor playing performance on the field—other baseball cranks and financiers were often willing to revive it. Thus a team or league’s legacy could be extended through several iterations via reorganizations, often involving many of the same cities and baseballists, until a viable situation arose. This is how the natural selection of various entities that would contribute to the eventual American League progressed between 1879 and 1899, before the Western League changed its name to the American League in late 1899.

Sullivan and James McKee did not bring their professional Northwestern League back in 1880 due to financial difficulties. Sullivan and Loftus decided to go with a semi-professional independent baseball team 1880–82. In 1881, Sullivan and Loftus took their Dubuque Rabbits to St. Louis to play a game against Chris Von Der Ahe’s St. Louis Browns. Dubuque surprised St. Louis by putting up a lively 2–1 fight on the pitching arm of Sullivan, but eventually lost it in the late innings 9–1, after Sullivan left the game. The St. Louis Globe Democrat said, “Sullivan, who pitches for the Dubuques, Loftus their second baseman, and Commiskey [sic], who guards the first bag, are a little team in themselves. They play a grand game.” The Missouri Republican observed, “Commiskey [sic], the Dubuques’ first baseman, played a splendid game, and is a whole team in himself.” Clearly Sullivan, Loftus, and Comiskey had made an impression. The following year, 1882, would see Comiskey playing for the St. Louis Brown Stockings in the first year of the newly formed American Association. (Comiskey would eventually captain and manage the Browns through 1889 and again in 1891, winning four pennants and a World Series.) In September 1882, Comiskey and the Browns made a trip north to Comiskey’s home in Dubuque to join in celebrating his wedding to Miss Anna Kelley at St. Raphael Cathedral Church. While in Dubuque, Comiskey and the Browns played two games against Sullivan and Loftus’s semi-pro Dubuques. St. Louis beat the Dubuques on the first day by a score of 9–5. Loftus and Sullivan scored all five of Dubuque’s runs. Game two the following day saw Loftus get three hits and a walk, scoring four runs in Dubuques’ upset over the Browns 7–4.

In 1883, Chris Von Der Ahe brought Sullivan to St. Louis to build him a winning team and manage the Browns. Sullivan brought Loftus with him to serve as team captain, and the team included several men from the 1879 Dubuque team including Comiskey, Bill Gleason, and Jack Gleason. Neither Loftus nor Sullivan would see the end of the 1883 season with the Browns, who would come up one game short of winning the 1883 pennant. In August of 1882, the long process to revive the Northwestern League had begun, with the goal of developing a league for “professional clubs of not sufficient strength to compete with the [National] League or the American Association clubs.” George Gray Jr. of the Grand Rapids Base Ball Association and William S. Hull of the Grand Rapids Democrat met in Milwaukee with a group of interested men from Northwestern cities in the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana. Milwaukee was tiring in their efforts to get a club back into the National League—having been dropped after 1878— and was interested in any stable professional league they could compete in. A list of proposed cities for the restart of the Northwestern League included Grand Rapids, Bay City, Milwaukee, Janesville, St. Paul, Dubuque, Davenport, Peoria, Rockford, Fort Wayne, and Indianapolis.

But because Loftus, Sullivan, and company had gutted the team to join the St. Louis Browns, Dubuque had to back out of joining the league. By the time the league was formed in November of 1882, only four of the originally suggested cities became members. The new circuit consisted of Grand Rapids, Toledo, Springfield, Fort Wayne, Saginaw, Bay City, Quincy, and Peoria. Elias Matter served as league president. The year 1884 would find Comiskey managing the Browns and Sullivan building yet another dominant majorleague team in St. Louis. This time Sullivan was organizing the St. Louis Maroons of the short-lived Union Association for team owner and league president Henry Lucas, while also helping Lucas organize the league. Sullivan would bring former Dubuque teammates Joe Quinn and Tom Ryder into the Maroons for the 1884 UA season. Quinn would have a long career as one of America’s favorite players in the major leagues between 1884 and 1901. Loftus, meanwhile, started the 1884 season as the highest paid player in the Northwestern League, serving as captain-second baseman for Milwaukee. Milwaukee had entered the expanded Northwestern League for the 1884 season. By June 16, Loftus had taken over the management of Milwaukee as well. The Northwestern League had a “second season” in 1884 with only four of the league’s 12 teams participating: Milwaukee, Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Winona, Minnesota. As the 1884 seasons progressed into late summer and fall for the Northwestern League and the Union Association, both leagues experienced teams folding from financial pressures, jeopardizing the completion of each circuit’s schedule. By September, Sullivan had moved from managing the Maroons to player-manager of the UA Kansas City Cowboys. With the Northwestern League’s second season over, Sullivan encouraged Loftus to bring Milwaukee into the UA, replacing the short-lived Wilmingtons. Sullivan would go 28–3 with St. Louis and 13–46 with Kansas City. Loftus managed Milwaukee to an 8–4 record in the UA. The St. Louis team Sullivan built for Henry Lucas would win the UA pennant with a record of 94–19, while Comiskey would take over as player-manager for the St. Louis Browns in the AA for the final 25 games of the season, going 16–7–2. (Over the next four seasons Comiskey’s teams would win four consecutive AA pennants and one World Series Championship.) On January 15, 1885, a winter meeting of the Union Base Ball Association (UA) was held in Milwaukee. League president Lucas and Justus Thorner were expected to attend. Thorner had been part owner and president of the Cincinnati Reds NL team in 1880, before they were replaced by the Detroit Wolverines for the 1881 NL season. Thorner, a founding member of the American Association and president of the Cincinnati Reds in 1882, was the founder-president of the Cincinnati Unions of the 1884 Union Association. But the only delegates to show up at Milwaukee’s Plankington House from the eight-team association were from the Kansas City and Milwaukee clubs. Warren White of Washington was there, not as a delegate representing the Nationals, but in his capacity as secretary of the UA. The reason for the no-show was Lucas and Thorner’s behind-the-scenes efforts to get their teams into the National League for the 1885 season. Lucas was successful, over Chris Von Der Ahe’s objections and in violation of the Tri-Partite Agreement between the National League, American Association, and the Northwestern League. His St. Louis Maroons would join the NL for the 1885–86 seasons.

Thorner’s request to join was denied, and the Cincinnati team folded. The city of Cincinnati would not see a team rejoin the National League until 1890, with Loftus serving as manager, when the Cincinnati Reds of the AA—originally founded by men including Thorner and Adam Stern in 1881–82, jumped leagues to join the NL. The club delegates at the Milwaukee meeting, though, included Sullivan and Loftus. Sullivan accompanied Kansas City’s Americus V. McKim, and Loftus accompanied Milwaukee’s Charles Kipp. Because the meeting was being held in Milwaukee, several of that club’s directors were also present. The order of business immediately turned to a proclamation denouncing Lucas and Thorner’s absences and a motion to immediately dissolve the Union Association was passed. With a unanimous vote, the Union Association was dissolved and “from its ashes rose the new Western league” proclaimed the Quincy Whig. Sullivan and Loftus, who along with Comiskey still lived in Dubuque, had a plan for a new league.

THE WESTERN LEAGUE

McKim, Kipp, Sullivan, and Loftus agreed to create a new league that January day in Milwaukee, and they called it the Western League. This was the first time the name Western League was used in baseball. During the meeting, a reply telegram was received from Indianapolis of the American Association stating their interest in joining the new league. The cities proposed were Milwaukee, Kansas City, Indianapolis, Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo. Sullivan was appointed ambassador and was sent forth to Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo to arrange clubs in those cities. Kipp was sent to Minnesota to see if the Minneapolis and St. Paul clubs of the 1884 Northwestern League would be interested in fielding a single team in the new league. Should Detroit be dropped from the National League— presumably to make room for St. Louis or Cincinnati— and join the Western League instead, the league would need another team to balance. Ultimately, Detroit stayed in the NL, St. Louis ended up joining the NL in 1885, and no opportunity for a Minneapolis-St. Paul team arose.

The Western League was officially organized by McKim, Kipp, Sullivan, and Loftus in Indianapolis on February 12, 1885. Delegates from Kansas City, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Cleveland, St. Paul, Toledo, and Nashville were present. The Western League’s inaugural season began on April 15 with Kansas City, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Cleveland, Toledo, and Omaha fielding teams in the new league. The Western League made it two months into its inaugural season before disbanding. Four teams had dropped from the league by then: Cleveland, Omaha, Toledo, and then the final straw Indianapolis. The Indianapolis team players were sold and transferred to Detroit, who had stayed in the NL. Sullivan had called a meeting for June 15 in Indianapolis to address the performance of Omaha’s replacement in the league (Keokuk, Iowa) and to review the applications of St. Paul and St. Joseph, Missouri, when Indianapolis exited. Similar to the ending of the Union Association, Sullivan of Kansas City and Loftus of Milwaukee were the only delegates in attendance, forcing an end to the first season of the Western League. Bill Watkins’s Indianapolis Hoosiers won the 1885 league pennant with Loftus’s Milwaukee team in second, seven games behind, and Sullivan’s Kansas City team in third, nine-and-a-half games back.

While Loftus took a break from professional baseball in 1886 to focus on his Dubuque businesses and growing family, Sullivan tried to revive the Northwestern League, which was not organized for the 1885 season, due in part to the national economic panic of 1884, and in part because of the formation of the Western League. Baseball, like other industries in the United States, struggled economically during the Depression of 1882–85.

Sullivan was successful in organizing six cities for the 1886 championship circuit of the revived Northwestern League: Milwaukee, Minneapolis, St. Paul, Duluth, Oshkosh, and Eau Claire, Wisconsin. With Loftus giving up the Milwaukee club for the 1886 season, Sullivan stepped in and managed the team in the city he and his parents had moved to when they first immigrated to the United States from Ireland circa 1855. Sullivan also served as the league’s president for 1886, just as he had for the Western League in 1885.

Sullivan’s Milwaukee club finished in last place at the end of the Northwestern League’s 1886 season. At the league’s end-of-season meeting in St. Paul in October, Sullivan was expelled from the league for trying to delay a game in Milwaukee by hosing down the field during the game, as well as for his and Loftus’s continued efforts to form a premier baseball league out of the best cities from the Northwestern and Western Leagues of 1883–86. At the time of Sullivan’s expulsion, he and Loftus were in Kansas City trying to drum up support for the revival of their 1885 Western League circuit.

THE WESTERN ASSOCIATION

In August 1886, a Sporting News headline touted a “new association” being formed at “a secret meeting” in St. Louis. The Sporting News indicated that “Among the prominents present were: Nin Alexander of the St. Joe Club; J.J. Helm of the Kansas City’s; Ted Sullivan of the Milwaukee’s; Thomas J. Loftus late of St. Louis, but now of Dubuque; Al. Cahn of the Evansvilles and James Thompson of Indianapolis. These gentlemen came here not only to hold a meeting but to meet certain St. Louisans in the interest of a new base ball [sic] association which is to be in the field in 1887. Loftus was long ago the originator of a scheme to form a new base ball association, its list to include the cities of St. Louis, Chicago, Indianapolis, Kansas City, St. Joe and Milwaukee.” The “certain St. Louisans” the group met with in all probability were Von Der Ahe and Comiskey. By the time the Western Association held its first meeting on October 26, 1887, Von Der Ahe and Loftus were listed as delegates representing St. Louis. As the Saint Paul Globe reported, “Loftus and Comiskey…with Von Der Ahe, are desirous of becoming factors in the new association.” Loftus and Comiskey, player-manager of the St. Louis Browns, owned 50% of the St. Louis Whites, while Von Der Ahe, owner of the Browns, owned the remaining 50% of the Whites.

The new “association” took the field as the Western Association in 1888. In 1887 Loftus continued tending to his businesses and family affairs while plotting his course back into professional baseball. Sullivan left Milwaukee after his expulsion to become a league umpire in the 1887 American Association. Sullivan would be succeeded as president of the Northwestern League and as manager of the Milwaukee club by James “Jim” Hart, former manager of the AA Louisville club and future president of the Chicago NL club, and another friend of Loftus. Hart and Loftus would find themselves at the center of the American League–National League controversy regarding moving Comiskey’s St. Paul Saints of the Western League into Chicago for the 1900 American League season. Throughout 1899, it had been indicated that Loftus’s Columbus Western League team would move into Chicago and Comiskey’s club would move to St. Louis, as the Western League transformed into the American League between 1899 and 1900. Eventually that would change when Loftus agreed to manage the Chicago Orphans for Hart, after a two-year courtship. Loftus took the Orphans job on the condition that Comiskey could move his team into Chicago. Hart’s blessing was required in accordance with the National Agreement. Another unusual condition of Loftus’s contract did not require him to give up ownership of his Columbus-Grand Rapids, soon-to-be-Cleveland, American League team going into 1900—although eventually he did. The contract also allowed Loftus to spend two weekends out of the month during the season back in Dubuque tending to his personal businesses if he desired. “As a matter of fact, the case is one of the most peculiar in baseball history,” an American League insider was quoted in the Kansas City Journal. “Loftus is given the privilege of remaining here two weeks and then going away for two weeks to attend to his outside interests, none of which he intends to dispose of, to take care of the Chicago club.”

The Western Association would begin with the close of the 1887 Northwestern League’s season. During the annual meeting of the Northwestern League at the Tremont House in Chicago, on October 24, several gentlemen unaffiliated with the league at the time, including Loftus, waited patiently for league president Jim Hart to end the meeting. The next day a new meeting was convened at the Tremont House by the organizers of the Western Association including Von Der Ahe and Loftus for St. Louis, Hart for Milwaukee, Sam Morton for Chicago, E.G. Briggs for Omaha, E.E. Menges for Kansas City, A.M. Thomson for St. Paul, and C.M. Sherman for Des Moines. The groundwork Loftus and Sullivan had laid back in 1886 drumming up interest in their league revival was finally coming to fruition after a one-year delay.

The 1888 season of the Western Association would put an end to the Northwestern League for three seasons, consuming that league’s three biggest cities: Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and St. Paul. Sam Morton of Chicago would serve as the association’s first president.

The 1888 Western Association would be the first league mentioned in The Sporting News 1918 American League birthday article that resembled “Ban Johnson’s” Western League from 1894–99—the precursor league to the AL. Starting in 1888, the terms Western Association and Western League were often used interchangeably, until 1894 when the senior league would solidify on the name Western League under Ban Johnson, as it began running simultaneously with the junior Western Association under Dave Rowe and WW Kent. The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, for example, announcing the formation of the 1888 Western Association, titled their article as “The New Western League” in their header and started out the first sentence of the article with, “The new Western Association has started its career under most favorable auspices.” The Dubuque Daily Herald reported Loftus’s leaving for the league meeting in Chicago by announcing in its Personals, “Tom Loftus left yesterday morning for Chicago to attend the Western League Association meeting.” The interchangeable usage of Western Association and Western League from 1888 to 1894 has added to the confusion in understanding the minor league predecessors of the American League. Loftus managed the 1888 Western Association St. Louis Whites until poor attendance and resulting financial difficulty forced a premature end to that team. After that, Loftus jumped to the American Association to finish out the 1888 season managing Cleveland. In 1889, Loftus took Cleveland into the National League. Loftus would spend three seasons in the NL, one with Cleveland and two with Cincinnati, before taking another break from baseball in 1892–93 due to the baseball war and the economic recession of the early 1890s.

Loftus’s business interests grew during his reprieve from baseball before becoming president of the Eastern Iowa League and president/owner of the 1895 Eastern Iowa League/Western Association Dubuque club. At the end of the 1895 Eastern Iowa League season, the Dubuques joined the Western Association. The 1895 Dubuques opened their season against Comiskey’s Western League St. Paul Saints in an exhibition game in Dubuque. Loftus’s Eastern Iowa League Dubuque team that season included young “Pongo Joe” Cantillon—future manager of rookie Walter Johnson. Cantillon first played in Dubuque in 1888.

Loftus joined Comiskey in the Western League under president Ban Johnson in the fall of 1895, when Loftus became owner of the Columbus Senators. Loftus and Comiskey both had gotten to know Ban Johnson, sports editor of the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, during their back-to-back stretch as managers of the Cincinnati Reds in 1890–91 and 1892–94, respectively, and served on the Western League’s board of directors with Johnson starting in 1896.

Baseball underwent a contraction 1891–93 as a result of years of in-fighting between the National League and the American Association and a national economic panic in 1893. The NL won the baseball war and put the AA out of business after the 1891 season, leaving only one major league. The Western Association of 1888–91 started going by the name Western League in 1892 and consisted of five of the eight clubs in Ban Johnson’s 1894 inaugural season as the league’s president.

BAN JOHNSON-ERA WESTERN LEAGUE

In October 1893, representatives from Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Toledo, and Indianapolis met in Chicago to restore the Western Base Ball Association (aka Western League) to its former glory. Henry Killilea of Milwaukee and Jimmy Manning of Kansas City, who were part of the Western League of 1892, and who would vote to change the name of the Western League to the American League in October of 1899, were part of the revival committee for the 1894 season. Manning, a former major league player, had been with Kansas City in 1887 and was part of Kansas City’s entry in the inaugural season of the Western Association in 1888.

In November 1893, at their meeting in Indianapolis, the revived Western League announced Johnson had been selected as league president. After the 1891 season, Cincinnati’s new owner John T. Brush had replaced the retiring Loftus with Comiskey as the Reds manager. As previously mentioned, both Loftus and Comiskey had gotten to know Johnson while managing the Reds. It was at Comiskey’s urging, and with Brush’s reluctant support, that the reconstituted Western League hired Johnson as their league president for the 1894 season. Comiskey would enter the Western League in 1895 as owner of the St. Paul club, and Loftus would do likewise in 1896 as the owner of the Columbus club. Comiskey and Loftus would serve on the Western League’s board of directors with Johnson, who would come to personally know and respect them as mentors.

In 1898, as the Western League was riding the height of its popularity under Johnson, Al Spink, founder of The Sporting News, and George Schaefer, both of St. Louis, started to promote among national baseball men the idea of a rival to the National League. Spink wrote Sullivan, who was managing Loftus’s Dubuque entry in the 1898 junior-circuit Western Association, about their idea. Sullivan was in favor of the idea and was willing to help. After a third team folded, the Western Association ended its season at the end of June, freeing Sullivan to meet with Spink. Around the time Sullivan was in Dubuque, Loftus brought his Western League Columbus Senators to Dubuque to play a league-sanctioned three-game series against Comiskey’s St. Paul Saints. Columbus took the series, 2–1. Ultimately, Columbus would move to Cleveland and St. Paul to Chicago for the inaugural American League season in 1900.

It is unknown how much Sullivan told Loftus and Comiskey in 1898 about Al Spink’s idea. It is highly unlikely the three friends and baseballists never spoke about it. What is clear is these three kindred spirits from the 1879 Northwestern League played pivotal roles as leaders in the leagues that preceded the American League. In 1899, Tom Loftus, Charley Comiskey, Ban Johnson, and the Western League owners would transform their minor league—the Western League— into the American League for the 1900 season; and then take on the National League establishment by reincorporating and declaring itself a major league for the 1901 season.

BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE

The “evolution” of the American League discussed in the 1918 Sporting News birthday article began with Ted Sullivan and his protégés Tom Loftus and Charley Comiskey in the Northwestern League of 1879. Sullivan and Loftus’s Western League of 1885, revived as the Western Association of 1888, were the next milestones in the journey towards the 1894 Western League. That association of Western clubs took on a new president—Ban Johnson—for the 1894 season; Johnson, along with Comiskey, Loftus, and other league magnates such as Jimmy Manning and Henry and Matt Killilea, reorganized their league into the American League. The minor leagues that predated it do not form a continuously linked chain of descendants from one league to the next, rather we could say it was natural selection at work, as various iterations were tried until a viable one succeeded. The desires of three friends—Sullivan, Loftus, and Comiskey—drove these early efforts, along with dozens of other baseball magnates, fanatics, cranks, and financiers who pushed for major-league quality baseball not just in the East, but in the West, giving rise to the American League.

Copyright – 2022 – The Lens of History – John T. Pregler. This story cannot be published, broadcast, rewritten or distributed without prior authorization from the author, The Lens of History, or SABR.