The years immediately after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, U.S. President Andrew Johnson and the Republican controlled U.S. Congress turned its attention to implementing the late President Abraham Lincoln’s Southern Reconstruction policies. President Johnson, along with the Democrats and conservative Republicans in Congress wanted a quick path to reconstruction through pardon and absolution of the Southern States. At the same time, the “Radical Republicans” in the United States, including Dubuque’s own U.S. Representative William Boyd Allison were pushing for harsher terms for Southern States and those who participated in the Confederacy during the recent War of the Rebellion.

As American cities both North and South began to settle back into life without civil war, the Young Men’s Literary Association of Dubuque, Iowa sponsored the city’s Winter Course of Lectures program.

As the Midwest and Western United States were being settled throughout the nineteenth century, one of the first forms of community entertainment that also provided a platform for community discussion of important topics of the day, as well as for speeches of an intellectual nature, was the local theater and lyceum, or lecture hall.

Dubuque’s Young Men’s Literary Association sponsored such speakers as German revolutionary and Union General Carl Schurz, who was an eastern newspaper editor at the time of his visit; New England abolitionist attorney Wendell Phillips; and “Old Man Eloquent”, Frederick Douglass, the African-American abolitionist and suffragist.

Frederick Douglass, a celebrated orator, author and former slave who “stole himself” from bondage, appeared in Dubuque no less than three times between 1865 and 1870 as he traveled the national lecture circuit. Douglass first appeared in Dubuque on April 20, 1866. At the time he was lecturing on the need for a favorable Reconstruction and on African-American suffrage. President Johnson had vetoed the Freedman’s Bureau bill on February 18, 1866, just two months earlier. The nation was now speaking about the impeachment of a president. And Frederick Douglass, the “great agitator”, a label he believed to be a call of duty, had a few thoughts on these matters he wished to share with anyone that would listen. And come to listen they did.

Many progressive citizens of Dubuque, the likes of which included Austin Adams, a direct descendent of Revolutionary Samuel Adams and a founding member of Dubuque’s Young Men’s Literary Association, and his wife, Mrs. Mary Newbury Adams, were surely delighted to hear Douglass was coming to Dubuque. Others in the city were not as excited. The Dubuque Daily Herald, a local Democratic paper that was anti-Lincoln during the war and anti-Reconstruction after the war, was sarcastic in their judgement of Douglass’s visit on the front page of their April 21, 1866 edition. The paper’s sharp jabs were targeted at the local progressive white Dubuque citizens as much as it was the “Negro” Douglass.

“In Dubuque, Fred, who is not such a bad fellow, and a heap better than most of those who, claiming to be white, now mourn that they were not black men not taken to the bosom of a radical family. The speculative gentlemen who exhibited him last evening at Julien Hall, considerately provided for him at the public hotel, making a special contract for so many rations and such an amount of lodging. Everybody stops at hotels, and why should not Fred Douglass, but then you will say the African man and brother should receive especial care having been rendered so helpless by emancipation. [sic]

The Herald knew Douglass was a paid orator sponsored by local “speculative gentlemen”, or event sponsors, or literary associations, whatever the case may be, and as such would have his full expenses paid, including meals and lodging. This was not uncommon for the times. Douglass was paid $100.00 by the event sponsors George D. Wood and his brother-in-law Hosea B. Baker. Wood was 2nd Vice President of the Young Men’s Literary Association in 1866. Both men were active members of the First Congregational Church of Dubuque – an active supporter of Dubuque’s Colored Christian Association in the 1860s – and would often help support community worthy projects and programs.

The city of Dubuque, like most established, growing and politically active cities in America, had a Democratic and a Republican leaning newspaper that often told very different sides to a story. In Dubuque, The Dubuque Daily Herald was the Democratic newspaper and The Dubuque Daily Times was the Republican newspaper. The Dubuque Daily Herald, a racist newspaper by twenty-first century standards, held views more in line with Southern Democrat newspapers of the time.

The Daily Herald, like a majority of American newspapers at that time, would refer to African-Americans, including Douglass, as “Negroes” or “colored” or sometimes “blacks” throughout its pages when speaking in general terms of the day. When the Daily Herald wished to stick Douglass or other African-Americans with a verbal dagger, however, they would maliciously refer to him as a “darkey” or “nigger” in its pages, as they did after Douglass spoke in Manchester, Iowa in 1867. These hateful words were used throughout the Daily Herald’s pages before, during and long after the Civil War.

So, it probably came as a surprise to many of the Daily Herald readers when the Herald’s article on Douglass’ first visit almost sounded sincere, even if fleeting, when they said Douglass was “not such a bad fellow.” That was the desired effect the Dubuque Daily Times hoped Douglass would have on many of the readers of the Daily Herald who might come hear him speak; the effect of doing away with many of the misconceptions about the black man and his abilities compared to his white counterpart by seeing his humanity in the flesh. In a brief article in their April 15th edition, the Daily Times proclaimed, “Fred. Douglass is to lecture in Dubuque on Friday evening next, April 20th. This will be a welcome announcement to many of our readers. His presence will do away with many prejudices that have been sincerely held against him and his race.” Indeed, this was the effect Douglass desired as well.

In the Daily Herald’s main article following the Douglass lecture, they opened with a sarcastic comparison of the Douglass lecture to a “side show” of the play Uncle Tom’s Cabin, being performed the same night as Douglass’ lecture at Dubuque’s premier theater and lecture hall, the Athenaeum, at the corner of 4th Street and Main Street. Because the Athenaeum was already committed, Douglass spoke that night at Julien Hall, in the same building the Young Men’s Literary Association was located at 5th Street and Locust Street. Dubuque’s own William Vandever, a former U.S. Congressman turned Union General in the late war, introduced Douglass.

The Daily Herald did not agree with Douglass’ premise that the country was in another crisis due to President Johnson “and that the strength of the country was again being put forth”, an assertion the Herald called a farce. After mocking Douglass’ belief that enfranchising the Negro was a key to a successful reconstruction, the Dubuque Daily Herald did fulfill a very small portion of the Daily Times fervent wish that Douglass’ “presence will do away with many prejudices that have been sincerely held against him and his race” with the remaining portion of their article.

The Herald goes on to cautiously praise Douglass, the man, while at the same time continuing to point out their belief he is incorrect in his position. “Without doubt, Mr. Douglass is the ablest champion of the colored race in this or any country. He is an earnest speaker and as such necessarily eloquent, not always candid but as he speaks in his own interest, much of his lack in this respect may readily be pardoned.” The article goes on to conclude,

“We commend his lecture as being nearer a logical and consistent argument than any politician pretending philanthropy can offer. Fred Douglass, with enough of the Negro blood in his veins to identify him with the black race, and the talent and honesty to make him a peer among men, is the most powerful champion of Negro suffrage in the nation, and the American people may without difficulty be induced to grant to him what they would unhesitatingly refuse to any other standing in his stead.”

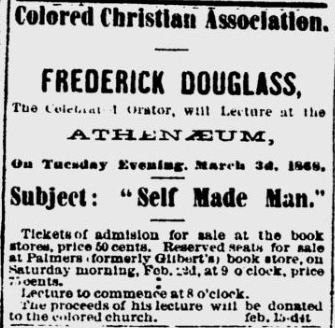

In 1868, the self-made man Douglass once again graced the lecture hall stages of Dubuque to give his by then famous speech on what it takes to be a “Self-Made Man”. On March 3, 1868, Douglass performed his oration at the Athenaeum theater at 4th and Main Streets. Douglass had first given this well-received speech in 1859 and had performed it periodically since.

Tickets for the program sold at local book stores for fifty and seventy-five cents. The box office profits from the event went to Dubuque’s Colored Christian Association, a local Methodist Episcopal organization with thirty-nine members in 1864. The Colored Christian Association was affiliated with the Young Men’s Christian Association of Dubuque and supported by different congregations of faith around Dubuque. According to the Daily Herald, the speech was well attended and well received.

The third and last time Frederick Douglass was known to lecture in Dubuque was on March 1, 1869 at the Athenaeum theater. His lecture was on “William the Silent”. The Dubuque Daily Times review of the lecture was not pleasing. “The lecture was a long, prosey [sic], disconnected harangue about the 80 year religious war in the Netherlands, with a meagre reference to William of Orange!”

Calling the speech a bore, the Times declared, “Mr. Douglass may lecture well of those things that touches him and nearly, but as a historical lecturer he is not a success.”

Not much else is known about Frederick Douglass’ visits to Dubuque, what he actually said in any of his lectures, or his interactions with Dubuque citizens, with the exception of Samuel Root, a nationally known portrait and landscape photographer living in Dubuque, Iowa since 1857.

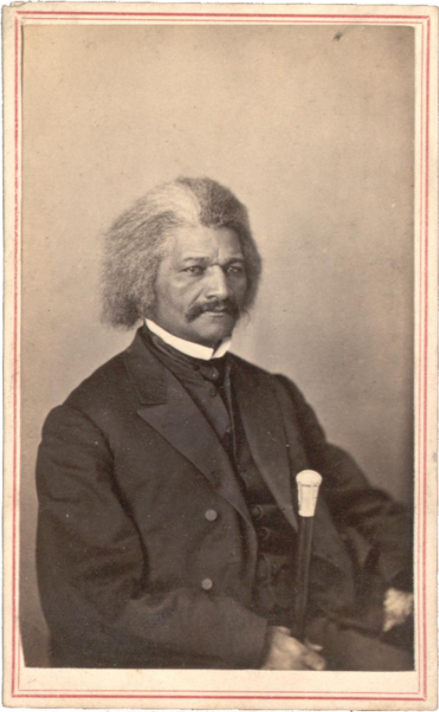

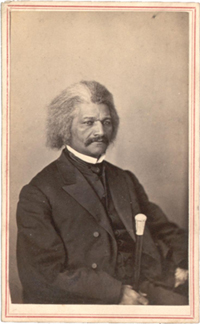

Frederick Douglass sought out photographers wherever and whenever he could, making him the most photographed person of the nineteenth century. Douglass knew if more white Americans could hear and see a real black man, and not just a caricature in a story or an engraving in the newspaper, it would help them understand and acknowledge the humanity of the Negro spirit and of his race. By going to local photographers, especially well-known photographers, Douglass knew his image would be sold as a curiosity and would be seen far and wide. He had hoped it might engage people in discussions on race, enfranchisement and racial equality for the African-American.

Samuel Root was the kind of photographer a person like Douglass would have sought out upon reaching a bustling city in the Northwest like Dubuque. Samuel Root and his older brother Marcus were well-known Daguerreian photographers who made names for themselves in New York City from 1849 to 1857. Samuel Root had taken well-known photographs of numerous famous people including statesman Henry Clay, the singer, “Swedish Nightingale” Jenny Lind, and General Tom Thumb, standing on a table leaning on the left shoulder of circus showman extraordinaire P.T. Barnum.

A carte-de-visite of Root’s image of Douglass is in the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History in New York City and it includes the artist’s stamp on the back of the CDV which states, “S. Root, Photographer 166 Main Street, Dubuque, Iowa”. It has been generally believed the carte-de-visite photograph of Frederick Douglass was taken by Samuel Root at his photography studio in Dubuque, sometime between 1865 and 1880.

Root moved his studio and his home from 166 Main Street in late 1867. Given Douglass spoke in Dubuque in 1866, 1868 and 1869, and Root moved his studio from 166 Main Street in 1867, it reasons that Root took the CDV portrait of Douglass in Dubuque during his 1866 speech on Reconstruction. It is possible Douglass had his picture taken on April 19th, 20th or 21st of 1866.

It is known with certainty from the local newspapers that Douglass was in Dubuque on the day he gave his speech, April 20th. It is also known from the newspapers that Douglass parted Dubuque on the 10:00 a.m. train the following day, April 21st, as he headed to Anamosa, Iowa for another lecture that evening. It is unclear if Douglass arrived in Dubuque on April 19th, the day before the scheduled Dubuque lecture, or on the 20th, the day of his lecture. The most likely scenario is Douglass came to Dubuque on one of the morning trains on April 20th. After finding his hotel and the lecture hall, Douglass probably walked the three blocks or so to 8th and Main Streets to sit for his portrait with Samuel Root, who was assuredly happy to oblige. It is unknown whether Douglass sought out Root or whether Root sought out Douglass to sit for the “picture-making”, as Douglass was fond of calling it. Nor is it known if Douglass and Root knew each other prior to their meeting in Dubuque in 1866.

The image taken by Samuel Root of Douglass that day shows a man who is impeccably dressed, with a serious, stern look on his brow and a light, relaxed grip of hand on his gold handled walking stick, suggesting to the viewer this is a proud, confident man who is sure of himself and his cause. A man who knows his every move is watched and scrutinized, as others look for faults they can ascribe to his entire race. A man who sits with the pressures of a righteous might he knows is guided by a higher hand bigger than himself. Root’s image of Douglass is one of the finer images known of Douglass. It is a well-exposed image with a clarity and crispness that brings depth to Douglass, the man, which can only be achieved by an expert photographer like Samuel Root.

In 1895, Frederick Douglass would meet up with Samuel Root one last time, this time forevermore, when he was laid to rest in Mount Hope Cemetery in his former adoptive hometown of Rochester, New York. Samuel Root was laid to rest next to his wife in a family plot in Mount Hope six years earlier.

Although Douglass was the most photographed person of the nineteenth century, only two CDV photographs of the Samuel Root image are known to exist. One is in the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History in New York City and the other is in the private collection of Ronald L. Harris.

Copyright – 2017 – The Lens of History – John T. Pregler. This story cannot be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without prior authorization from the author or The Lens of History.

My wife Cheryl and I recently visited the Samuel Root cdv image of Douglass in the Gilder Lehrman Institute archives at the New York City Historical Society Museum in NYC. The image is more impressive in person and it was a real treat to be able to hold it. A special ‘Thank You’ to Alinda Borell at GLI for coordinating the visit!