In 1848 the Wisconsin Territory joined the Union of States as Wisconsin – America’s 30th state. In the first few years of the state’s legislature a bill was passed creating the position of State Geologist, which was filled by Professor Edward Daniels. The first major task Prof. Daniels undertook after getting his office organized was a state geological survey.

The purpose for the creation of the position of State Geologist and the conduct of a geological survey was to identify the enormous economic potential the vastness of the state of Wisconsin had to offer. Wisconsin was competing with other Midwestern states in an attempt to draw people, companies and capital to the burgeoning state from the eastern coast of the United States. In 1850 Wisconsin had a population of 305,391 inhabitants and a wealth of natural resources waiting to be cultivated in the form of lead and zinc, iron ore, exposed granite, soft pine and hardwood timber for lumber, and ample farm fields of wheat, oats, corn, hemp and tobacco.

Prof. Daniels started his survey in the southwest portion of the state of Wisconsin around the mineral rich lead mining district which first brought settlers to the area in the 1820s. The rush to the areas of Galena, Illinois and Mineral Point and Dubuque in the Michigan Territory after the Black Hawk War of 1832 to mine zinc and lead ore is considered the first “mineral rush” in the United States, predating the California gold rush of 1849.

When Prof. Daniels’ report to the state legislature came out in 1854, Daniels outlined his processes and the layers of earth’s stratification they penetrated during the study. He went on to aligning the layers of stratification to ages gone by and documented the different fossils of vegetation and animal life found from the different periods in the stratification.

“But the fossils of greatest interest peculiar to this deposit, are the gigantic bones which have at several places been found imbedded in it. Those found at Fairplay belonged to an Elephant and Mastodon, and similar ones were dug up at Potosi. The remains of an elephant have also been discovered at Sextonville, Richland County. Those discoveries prove that in ages immeasurably remote the Elephant and Mastodon roamed over Wisconsin, and found favorite places of refreshment and repose on our hills and valleys, and even upon the sites of our populous towns.”

Prof. Daniels went on to report that, “Within the last ten years, as many as ten or twelve skeletons of these huge extinct animals have been discovered in various parts of the lead region, and almost invariably in the fissures in the limestones imbedded in the clay which fills the orifices, and forms the matrix for the veins of lead ore. “

“The bones being found in the clayey matrix of the veins, and ores associated in the clay with them, proves beyond a doubt, that the Mastodon species became extinct before the lead ore was deposited in these crevices.”, says Daniels. Stratification of the earth over time creates different layers of materials within the stratified layers. One of those layers from roughly 10,500 to 11,000 years ago, a layer of clay found about 30 feet deep in the veins, was ideal for preserving fossils.

“We speak of our Indian mounds as ancient; and, relatively, they are – but compare them with the age of these gigantic mammilla! Yet these mammilla are themselves but recent creations in geological chronology.” Daniels said. “The lakes and rivers from which they drank are now dry; and the forests amid which they wandered, and upon whose luxuriant vegetation their colossal forms were fed, have disappeared forever.”

In 1854, speaking more specifically about bones found around Grant County, Wisconsin, Prof. Daniels said the bones found at Fairplay were in the possession of J. Potts, Esquire, of Galena, Illinois. The bones found by Luther Irish in Sextonville, Richland County, Wisconsin included bones and a tooth. Unfortunately in most instances only one or two teeth would survive. Professor Daniels stated, “The bones were so far decayed that they crumbled to dust as soon as the dust was removed from them; otherwise the entire skeleton of the elephant might have been secured.”

After examining a tooth found on the Potosi, Wisconsin property of a Mr. Hull, Prof. Daniels exclaimed it “proved the owner of the huge bones to have been an elephant.” The reason for the belief these teeth and bones belonged to an elephant was twofold. First, the study and understanding of fossils and the study of events throughout earth’s history by way of studying layers of stratification was in its infancy and they did not know what they did not know at the time.

Second, teeth and bones of mastodons where found throughout sections of the United States, from Alaska to Florida, from the Great Lakes region down into Central America dating back to the very early Colonies. One such tooth found in South Carolina was strikingly familiar to many of the slaves on the plantation where it was found.

The slaves believed the tooth was similar to the African elephant they had known prior to their capture and forced removal to North America.

In four areas around Sinsinawa Mound, Wisconsin, miners prospecting for veins of lead ore found portions of skeletons “of the Mastodon species.”

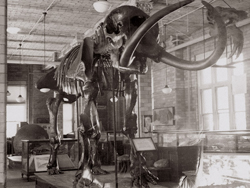

In 1897, 43 years after Professor Daniel’s first report, Harry, Chris, Verne and Clyde Dosch were checking on flood damage on their father’s property along the Mill Creek near the village of Boaz, in Richland County, Wisconsin. While walking along the banks of the creek they saw large bones sticking out of the earth and mud. Unlike prior Wisconsin discoveries, this time the bones were largely intact and the Dosch brothers were able to recover two-thirds of a mastodon skeleton; minus the tusks. Additional mastodon bones were discovered near Fennimore, Wisconsin a year later and would be used in combination with the bones discovered in Boaz to create ‘The Boaz Mastodon’. The Boaz Mastodon is on display at the UW-Madison Geology Museum, leaving one to wonder, how many more of these giants rest unassumingly under our feet, in our fields and along our bluffs, valleys and river banks?

No elephants or mastodons were harmed in the writing of this article!