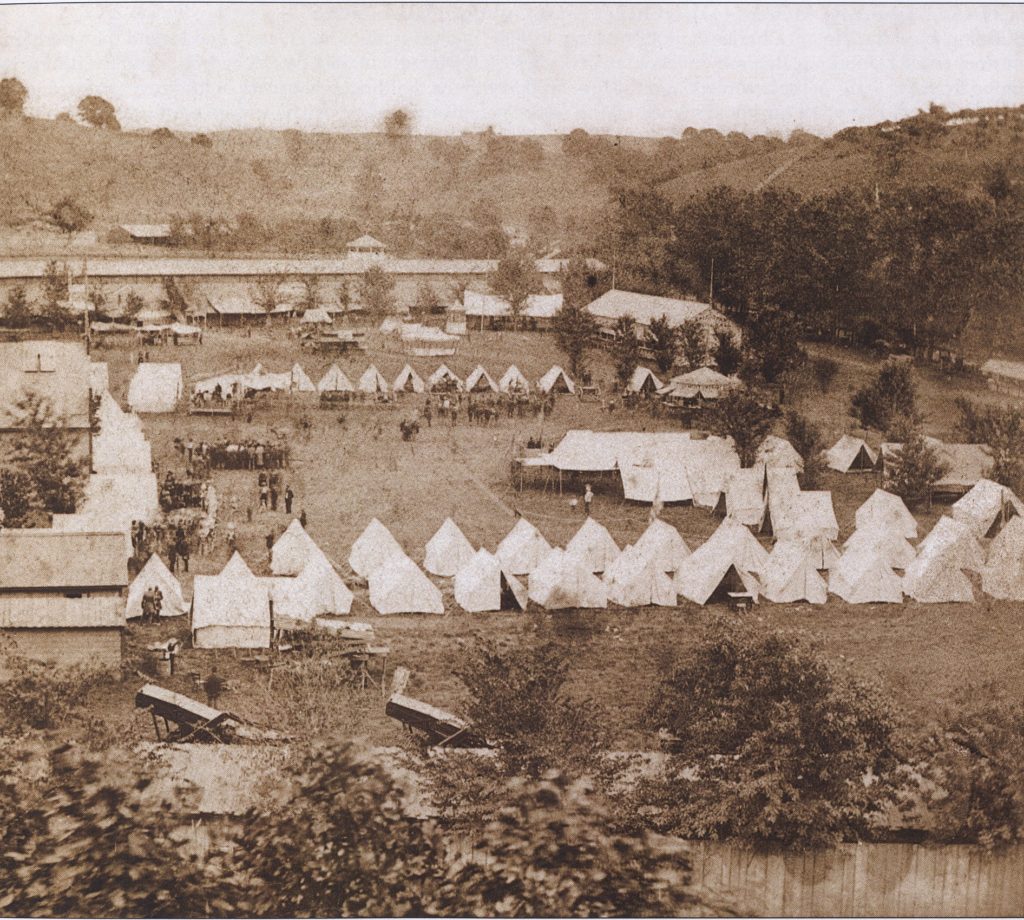

In the spring of 1884 Dubuque, Iowa was alive with military splendor as the city played host to the largest military encampment in the United States since the end of the Civil War. Dubuque, a city of 22,254 inhabitants in 1880, prepared for 20,000 to 30,000 visitors expected to descend upon the Mississippi River town to watch the events of the encampment being held at the fairgrounds, north of the city.

In a first of its kind, military units from the Federal Army and from the states National Guard rendezvoused in Dubuque from June 16-21, 1884 to participate in joint military drilling, drill competitions, and a large “sham” battle at the close of the encampment.

Parades were held throughout the week with the main procession of soldiers in the grand parade on Tuesday, June 17th stretching down Main Street from 1st Street all the way to 17th Street. Music filled the air from military bands parading about town throughout the week. Flags and red, white and blue bunting decorated City Hall and several city firehouses. The office of Henderson, Hurd & Daniels at 608 Main Street displayed an old Civil War battle flag provided by Col. David B. Henderson, who was a nationally known Civil War veteran in his second year as a U.S. Congressman from Iowa.

Cavalry from Milwaukee and St. Louis rode their fine steeds in the grand parade. Eleven different artillery units from as far away as New Orleans joined the encampment with 30 cannons and artillery pieces present for the sham battle. The 4th and 5th U.S. Artillery were both on hand with heavy cannon. The Clinton (Iowa) Gun Squad brought a cannon captured from Confederate forces at Vicksburg during the late Civil War that they used during the sham battle.

Twelve different infantry units from around the country made up the bulk of the men encamped at the fairgrounds in make-shift regimental barracks and tent campsites. The 4th U.S. Infantry was the lead Federal infantry unit encamped. Militia and infantry units from different states’ National Guards included the Mobile Rifles from Alabama; the Tredway Rifles of the 3rd Missouri Infantry; the National Rifles from Washington, D.C. and the Busch Zouaves from St. Louis, Missouri. Seven military bands and four drum corps, including a Dubuque drum corps, provided music for drilling, marching, parades, concerts, dancing and the sham battle.

The 3rd Missouri Infantry had history with the city of Dubuque dating back to the start of the Civil War. The 3rd Missouri, Company I, consisted of Iowa soldiers who were recruited into services in Dubuque in 1861, originally for the Lyon Regiment, 19th Missouri Infantry. The 19th Missouri would merge with the 3rd Missouri Infantry shortly after it mustered into service. All of the Dubuque, Waverly, Dyersville and eastern Iowa boys coming from the 19th Missouri were assigned to the 3rd Missouri’s Company I. A notable member of the Tredway Rifles at the Dubuque encampment was the 19-year-old son of General William Tecumseh Sherman, Philemon Tecumseh Sherman.

Joint encampments of states’ National Guard units were not uncommon in 1884 and a large national encampment of the National Guard from multiple states was held in 1883 in Nashville, Tennessee. The Nashville encampment was led by Brigadier General C.S. Bentley of the Iowa National Guard. In 1884 military drilling and instruction did not follow a consistent nationwide standard. Encampments were a way to bring different units from around a state, or regionally from multiple states together to share ideas, techniques and to become more cohesive in the event they are called together in service of a larger cause. Some state guard units drilled using outdated techniques from the Civil War. Some units made up of members of German descent used Prussian drill techniques. Other units used modern techniques and tactics. Over time, Federal and National Guard officers were seeing the need for greater cooperation and believed joint encampments were a way to start standardizing drill techniques, share information and build a working relationship between the Federal Army and the collective states National Guard.

A big proponent of a joint federal-state encampment was Dubuque resident, Civil War veteran, and commander of the “Northwest Brigade” of the Iowa National Guard, Brigadier General C.S. Bentley. General Bentley was elected chairman of the Dubuque encampments Committee of Arrangements and worked long and hard to organize every aspect of the national gathering. General Bentley was already nationally known for organizing successful National Guard encampments, including the prior year’s Inter-state encampment in Nashville, Tennessee.

Assisting Brig-Gen Bentley with the Dubuque encampment by order of Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln was Captain William H. Powell of the 4th U.S. Infantry out of Fort Omaha, Nebraska. Captain Powell was a career military man going back to the start of the Civil War where he saw action in the Eastern Theater at 2nd Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. Upon Powell’s arrival in Dubuque he immediately took over preparations for the camp at the fairgrounds and started the plans for the sham battle scheduled to take place at the end of the encampment.

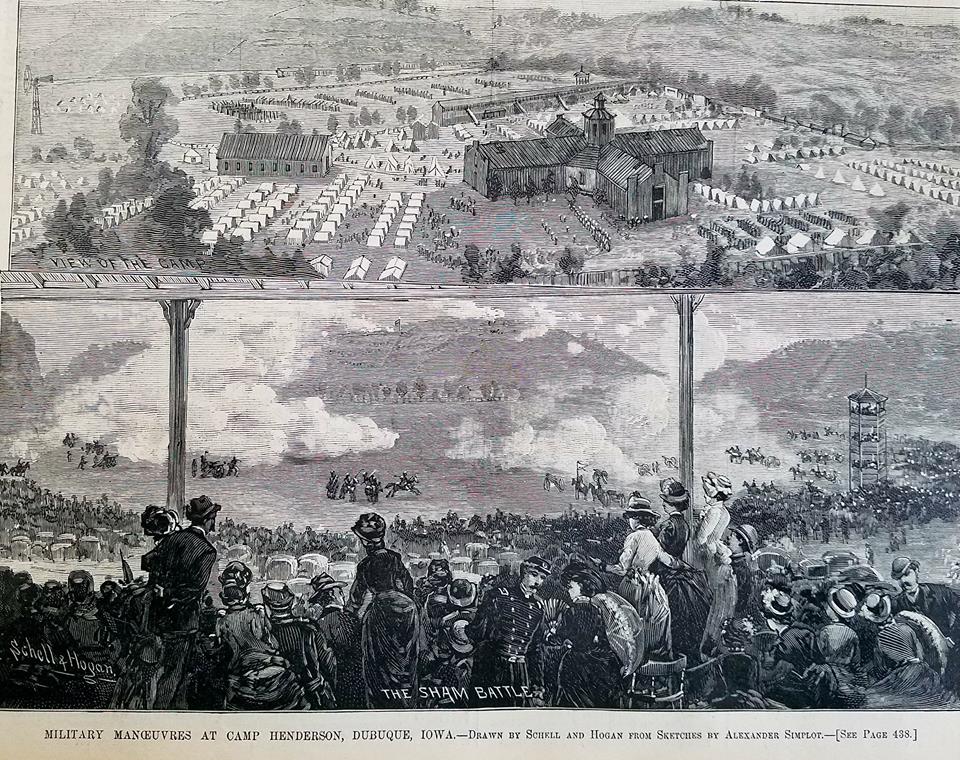

Military observers and other honored guests were among the thousands of spectators who came to Dubuque to see the great military gathering. Retired career military officer and Confederate General E. Kirby Smith was on hand as a guest of Dubuque resident William Andrew. General Winfield Scott Hancock, who gained national fame at the Battle of Gettysburg and was the Democratic Party’s 1880 nominee for President of the United States was invited, but had to regrettably turn down the invitation due to a prior engagement. Governor Rusk of Wisconsin and Governor Sherman of Iowa both made appearances at the encampment. Harper’s Weekly, a nationally distributed journal of the time, asked Gen. Bentley to hire a local artisan photographer to capture images of the encampment for the magazine. Bentley turned to local Dubuque war artist, Alexander Simplot. Simplot made a national reputation during the first half of the Civil War with his sketches from the Western Theater, including the very first published pictures related to the Civil War, appearing in the May 25, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly. Other photographers from around the Midwest attended the encampment, including Dubuque photographer, Samuel Root, and St. Louis photographer, John A. Hazenstab.

Additional military observers on hand for the national encampment included Gen. John Gibbon of the 7th U.S. Infantry – acting commander of the Department of the Platte; Col. William P. Carlin of the 4th U.S. Infantry – Fort Omaha; Col. John E. Smith of the 14th U.S. Infantry (retired); Col. E. C. Mason of the 4th U.S. Infantry – Inspector General of the Department of the Platte; Lt. Col. D. W. Flagler – Commander of Rock Island Arsenal; and the Adjutant Generals’ of Iowa, Missouri and Minnesota. Also in attendance was Major George Clitherall – Alabama National Guard (retired) and a founding member of the Mobile Rifles in 1836.

General Gibbon’s attendance offered the opportunity for a reunion of sorts in Dubuque with an old Civil War brigade he used to command, the Black Hat Brigade of the West; made up of regiments from Wisconsin, Michigan and Indiana. The Black Hat Brigade included five companies of men from across the Mississippi River from Dubuque, in Grant County, Wisconsin. Companies C and I of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry and Companies C, F and H of the 7th Wisconsin Infantry were Grant County boys who were part of Gibbon’s brigade that would go on to be immortalized as the Iron Brigade through the Battles of Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg.

General Gibbon saw action with the Iron Brigade up to and including the Battle of Antietam before being promoted. Gibbon participated in the Battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, among others. In November of 1863, Gibbon attended the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, where he heard President Lincoln deliver his famous address. Gibbon would finish out the Civil War in the front parlor of Wilmer McLean at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Gibbon would go on to participate in the Indian Wars of the 1860s and 1870s and was in command of the 7th U.S. Infantry when it arrived in time to bury the dead the day after General George Armstrong Custer lost his battle at the Little Big Horn in Montana, just eight years earlier. With the possible exception of E. Kirby Smith, Gibbon was the most notable military observer at the Dubuque encampment.

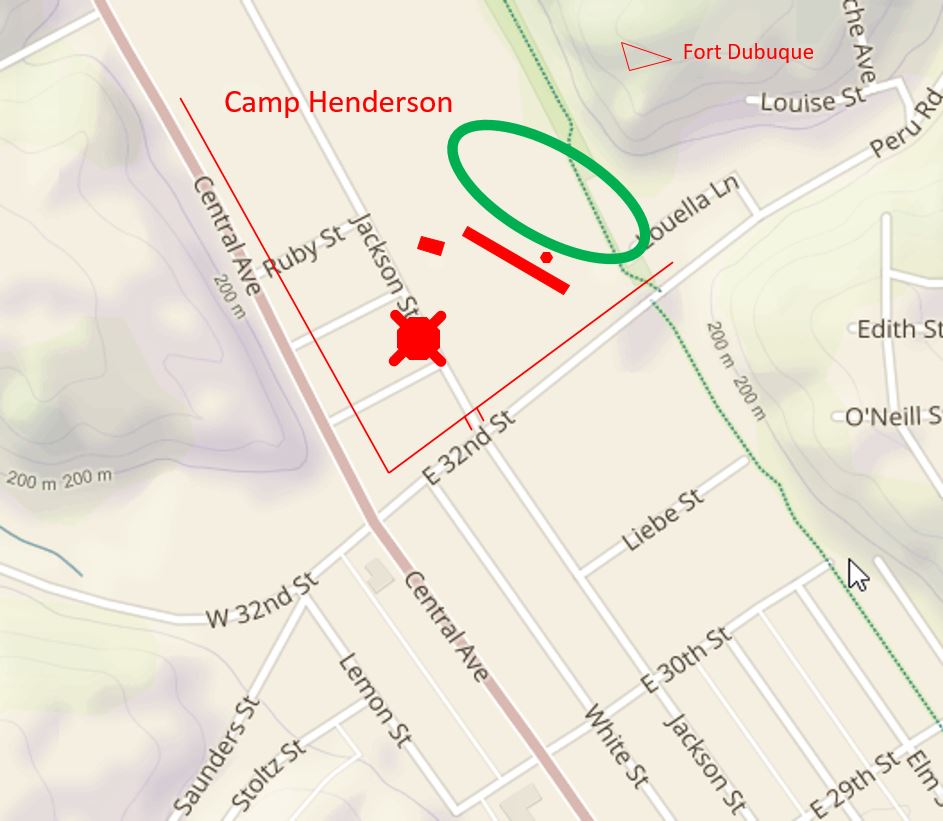

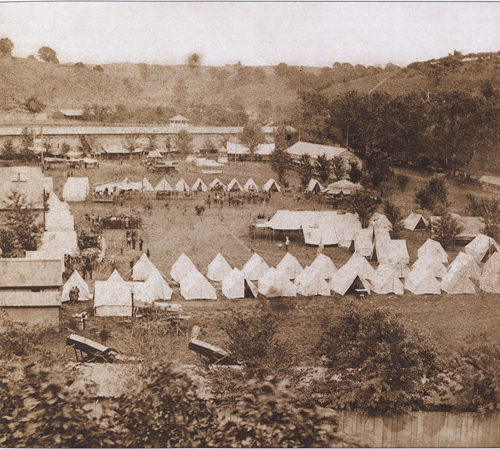

The Dubuque Fairgrounds, north of the city heading out Couler Avenue (present-day Central Avenue), was selected by the encampment Committee of Arrangements as the location to house the soldiers, hold the military drilling and conduct the sham battle. On the first day of the encampment, General Order No. 1 from Gen. Bentley proclaimed “The national encampment at Dubuque will be known as Camp Henderson” in honor of Dubuque’s Col. David B. Henderson. Henderson, as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, along with fellow Dubuque citizen U.S. Senator William Boyd Allison, aided in the efforts to make the joint federal-state encampment in Dubuque a reality. They left it up to fellow Dubuquer Gen. Bentley to make the encampment a success.

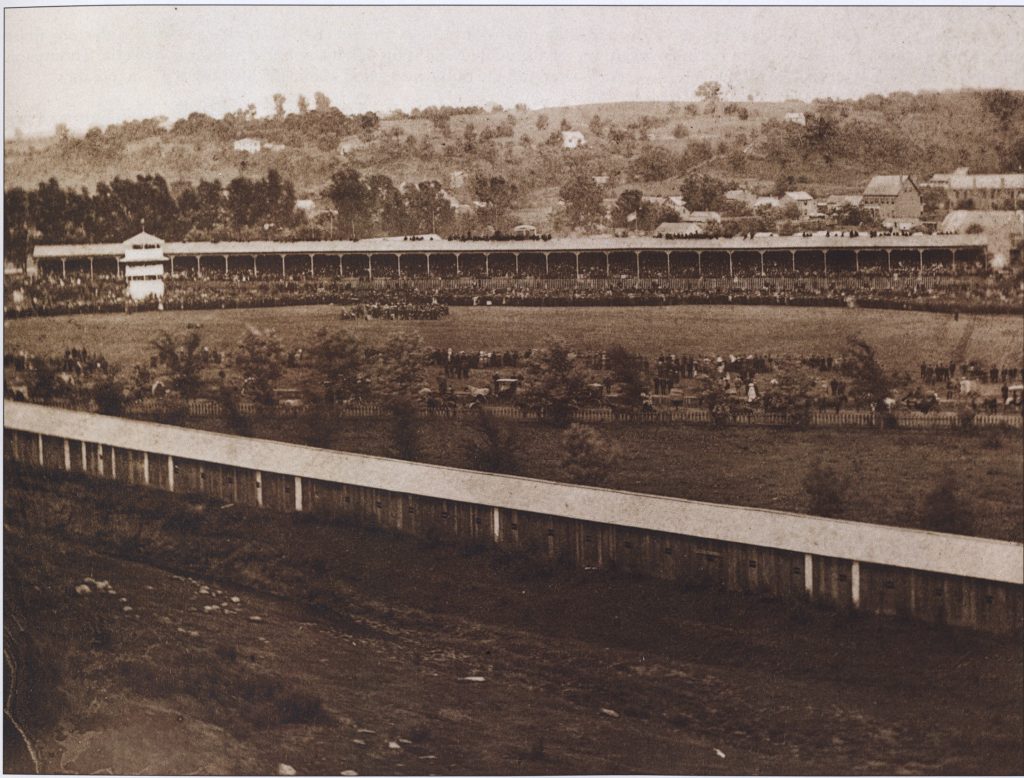

The scheduled program for the encampment consisted of daily guard mounting and dress parades accompanied by military bands performing for the crowds. Tuesday, June 17th would consist of a grand city-wide military parade followed by various company drilling exercises. Wednesday, June 18th would have consisted of competitive drilling of the various infantry, had the day not been rained out. Thursday, June 19th would consist of flying artillery drills and Gatling gun practice. The 19th would end with Cavalry drills and a band concert. On Friday, June 20th, the sham battle and assault on Fort Dubuque would occur, bringing the National Military Encampment to a near close.

During the course of the week, the drilling competitions resulted in Company F of the 1st Alabama Infantry, better known as the Mobile Rifles, winning first prize for the infantry competitive drills. Their prize consisted of a gold enameled badge for each member of the winning company.

The Busch Zouaves of Saint Louis, Missouri won the Zouave competitive drill. Their prize was a “unique ice-water set” of silver. Inscribed was “First Premium won by the Busch Zouaves, Dubuque, Iowa, June 16th, 1884”.

The Milwaukee Light-Horse Squadron won the prize for the cavalry competitive drill. Their prize consisted of a trophy 18 inches in diameter and made of silver, bronze and other metals. Inscribed was “To the best-drilled cavalry company; Dubuque, June, 1884”.

The Gatling gun demonstration by Skipwith’s Battery from Saint Louis consisted of 4,800 rounds being fired in one minute from four different guns to the delight of all who saw or heard. The drills and demonstrations were brought to a thunderous close with rapid maneuvers performed by Light Battery D of the 5th U.S. Artillery and Light Battery F of the 4th U.S. Artillery. The Washington Artillery from New Orleans, Louisiana included in its ranks Dudley Selph, widely considered the best long distance shot in North America and Europe. They won the artillery competitive drill. Their prize was a silver ice-water set.

With the demonstrative and competitive drilling complete, Friday, June 20th brought the highlight of the week – the sham battle. The object of the sham battle was to either assault or defend Fort Dubuque, depending under whose command you were assigned. Fort Dubuque was a makeshift triangular fort with each side measuring 100 feet in length and 4 feet in height. The fort was located on the crest of a prominent hill to the north of Camp Henderson at the intersection of two valleys. The fort was guarded by two 3-inch guns and two 12-pound howitzers.

Capt. Powell of the 4th U.S. Infantry commanded the defensive forces of Fort Dubuque during the battle and Lt. Col. Mason, also of the 4th U.S. Infantry, commanded the attacking forces. During the battle the defenses put up a good fight but eventually Fort Dubuque would inevitably fall, leaving Capt. Powell no other choice but to blow up Fort Dubuque with 50 pounds of gun powder placed in a shaft in the ground located within the fort. Shortly after the grand explosion and the capture of the fort’s flag, the Civil War regimental flag of the 9th Iowa Infantry, the bloodless battle came to an end.

The estimated 20,000 plus spectators who came to Dubuque by train, boat, horse and on foot had experienced an action packed week unlike anything Dubuque, or any Midwest city had seen before. The military encampment during peace time presented a carnival-like atmosphere for both soldier and spectator alike.

The daily events at Camp Henderson were not the only entertainment taking place on the fairgrounds. A circus was set up and performing at the north end of the grounds. Temporary gambling licenses were issued to numerous vendors in town. Some set up games of chance at the fairgrounds. Other local Dubuque establishments, namely saloons, received licenses and offered games of chance for the duration of the encampment. The local temperance movement, which believed vices like gambling and drink fed off of one another, was not pleased. “The number of gambling licenses Issued this present week is a matter of grave offense to a large majority…” read the Dubuque Daily Times. Of greatest shame was “one of these gaming institutions” on Main Street between 6th and 7th Streets which was “kept open day and night.” Captain Powell would later remark about the soldiers conduct in Dubuque, “Although the camp was surrounded by saloons and drinking places of all kinds, I did not see a single soldier drunk or hear of a disorderly proceeding. To the presences and example of the Regulars in this respect I attribute much.”

For those less inclined towards vice, a gathering at a local private residence may be more of your liking, or you may have taken in one of the many events going on in the evenings at the local roller-skating rinks or at the opera house. Clark’s Rink on Main Street between 9th & 10th Streets held “war concerts” several nights in a row with 150 “trained voices” singing patriotic songs. The performance included a “Negro quartette” that was “loudly encored time and again.”

The Couler Avenue Rink on Couler Avenue (now Central Avenue), just north of Sanford Street, promoted the skating Jones Sisters and their skate dancing. Their “grand march of the broom brigade” left the audiences rolling in laughter. On Thursday night, the Couler Avenue Rink held a large military ball. Both roller rinks had open skating for the public during the day and some evenings during the encampment.

With so many visitors to the city, and given the carnival-like atmosphere with open gambling all around, it is no surprise the daily newspapers included individual stories of pickpockets and robberies. The June 22nd edition of the Dubuque Daily Times listed the names and stories behind eleven different pickpockets nabbed in the act. Matthew Kirwin and John McLain were arrested for stealing a pocketbook from an attentive auditory. They were arrested by a soldier, Richard Robinson, of the 4th U.S. Infantry and held until local police could take them. The Burke Light Guards also escorted two pickpockets to the “calaboose”. Albert Carr observed a thief stealing a ladies gold watch and nabbed him by the neck in the amphitheater stands. The thief struggled, a fight ensued and the crowd got involved. According to the Dubuque Daily Times, “A rope was produced and the fellow would have been hung had not officers appeared.”

Aside from a few bad apples, the National Military Encampment at Dubuque was a success on all accounts. Many sang the praises of North and South working together in military harmony. Some pointed out the fact that a former Confederate unit, the Washington Artillery from New Orleans, captured the original Civil War battle flag of the 9th Iowa Infantry, used atop Fort Dubuque, with no animosity or disrespect shown towards one another.

The Grand Army of the Republic’s Joseph A. Mower Post commander from New Orleans messaged the commander of Dubuque’s Hyde Clark Post after reading about the encampment and the Washington Artillery in the local newspapers. The message read, “Joseph A. Mower Post sends thanks for your kind treatment of our ‘Johnny Rebs’. – J.E. Bissell, Commander.” Former Confederate General E. Kirby Smith echoed those sentiments.

In his report on the National Military Encampment to the Adjutant-General of the U.S. Army, Capt. William H. Powell remarked, “In the report of my visit to the encampment of the Iowa National Guard last year I expressed the belief that by encamping a portion of the regular troops with the National Guard each year, beneficial results would follow. My expressed belief has been fully realized at this encampment.” Due to the success of the Dubuque encampment, greater efforts began in earnest to standardize and share information and techniques between the regular Army and the states National Guard through joint training.

One of the recommendations Capt. Powell made coming out of the Dubuque encampment regarding equipment was the adoption of the rubber overcoat with sleeves as part of approved Army clothing.

Capt. Powell had seen Iowa National Guard units wearing rubber raincoats the year prior at the Iowa National Guard encampment, at which event it rained. Capt. Powell saw them again in action during his rain-filled week at the encampment in Dubuque.

In Powell’s report to the Adjutant-General he states, “In rainy weather the overcoat is too heavy for summer, and the poncho too ungainly in appearance, and does not fully protect the soldier, particularly in driving rains, while the rubber coat with sleeves is not only uniform in appearance, but enables the soldier to handle his piece with ease.” He goes on to add, “In addition to this, a very serviceable black rubber helmet is manufactured and sold at the low price of 35 cents, which, added to the coat, to take place of the poncho, would make the uniform complete.”

After the encampment ended on June 21st, temporary structures erected for Camp Henderson were taken down, the wood re-purposed, and the city fairgrounds returned to normal. The city would return to regular daily life once the 20,000-plus visitors had left. All that would remain were the trophies won in competitive drilling and memories of the participants and witnesses. Over the course of several decades, they too would be lost to time! …

POSTSCRIPT

… Until now! In March of 2017, I did a simple search on eBay for all things “Dubuque”. One of the many auction listings that appeared was for an ”1884 CIVIL WAR TROPHY BUSCH ZOUAVES 8th MISSOURI INFANTRY PRESENTATION PITCHER”. The item description went on to read, “This is a scarce civil war Busch Zouaves (8th Missouri Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865) 1884 Huge trophy Presentation Water Pitcher.” The description listed all the major engagements the 8th Missouri fought in during the Civil War and concluded with an inscription found on the pitcher, “First Premium won by the Busch Zouaves, Dubuque, Iowa, June 16, 1884.”

As a Dubuque historian and researcher, I immediately knew upon reading the inscription that the pitcher was unrelated to the Civil War. Being familiar with Camp Henderson and the 1884 encampment, I suspected this must have been a trophy for an event held at the Dubuque encampment. Since I was the only bidder, I won the eBay auction and the “unique ice-water set of silver” has since returned home to where its story began – Dubuque, Iowa – and where its story may be told once again.

In following up with the seller, I asked if he knew what happened to the accompanying goblets that go with the pitcher, making it a set? I also asked if he knew any of the wonderful piece’s history or provenance. The seller only knew for sure what he read in the inscription. He said the pitcher and stand were in a box that was filled with other unrelated items and stacked among other boxes in an abandoned storage locker he had purchased at auction in Oklahoma; the goblets nowhere to be found. The seller knew nothing more.

Upon further investigation, I learned the ice-water pitcher and goblet set were procured for the encampment from A.R. Knights & Co. It was described in the Dubuque Herald newspaper as a “tilting pitcher and goblets, in repose or raised work, with a magnificent base.” The ice-water pitcher set was on display in the A.R. Knights & Co. store front window the week of the encampment. A. R. Knights & Co., a wholesale jeweler specializing in diamonds and silverware, was owned and operated by Alonzo R. Knights of Dubuque. Knights’ store occupied 708 to 714 Main Street in Dubuque.

It was also learned that the Busch Zouaves of St. Louis were invited to the encampment and hosted by the Brewers’ Association of Dubuque. The unit took their name in honor of the famous St. Louis brewer Adolphus Busch, who in return liked to promote the unit as a means of promoting himself. The week of the encampment, Busch left for Germany to make plans to tour the continent in 1886 with the Busch Zouaves to show off their superior military drilling techniques. The Zouaves were known for their lightning riffle drill, which was performed by Sergeants English and Gleason at Dubuque’s Opera House the week of the encampment.

With my rediscovery of the ice-water pitcher, I concluded upon learning its history that the best way to honor its memory was by telling the story of its journey. And so the memories of the sham battle and the trophies valiantly won on the drilling fields of Camp Henderson long ago, once lost to time, are rediscovered and told here once again.

Location of Camp Henderson

Camp Henderson was located on the site of Dubuque’s first fairgrounds and driving park, north of the city. A driving park was a common term for a horse racetrack. The Iowa Intra-State Fair Association grounds where the encampment was held were located along Couler Avenue (present-day Central Avenue) and Peru Road (present-day E. 32nd St.) heading north along Couler Avenue. and heading east along Peru Road.

Fascinating story. I never knew of Camp Henderson and it was so close to the part of town that I grew up in.

Great job John! Rediscover Dubuque History!!